Table of Contents

Everyone talks about FOMO. The fear of missing out supposedly drives investors to make stupid decisions, chasing returns they see in their neighbor’s portfolio or on financial Twitter. Buy high, sell higher, or so the dream goes. But there’s a quieter, more insidious problem that destroys more wealth and causes more pain. It’s the opposite of FOMO. It’s the desperate clinging to what you already own.

We fall in love with our stocks. And like most love affairs that start with promise and end in denial, this one costs us dearly.

The Peculiar Psychology of Ownership

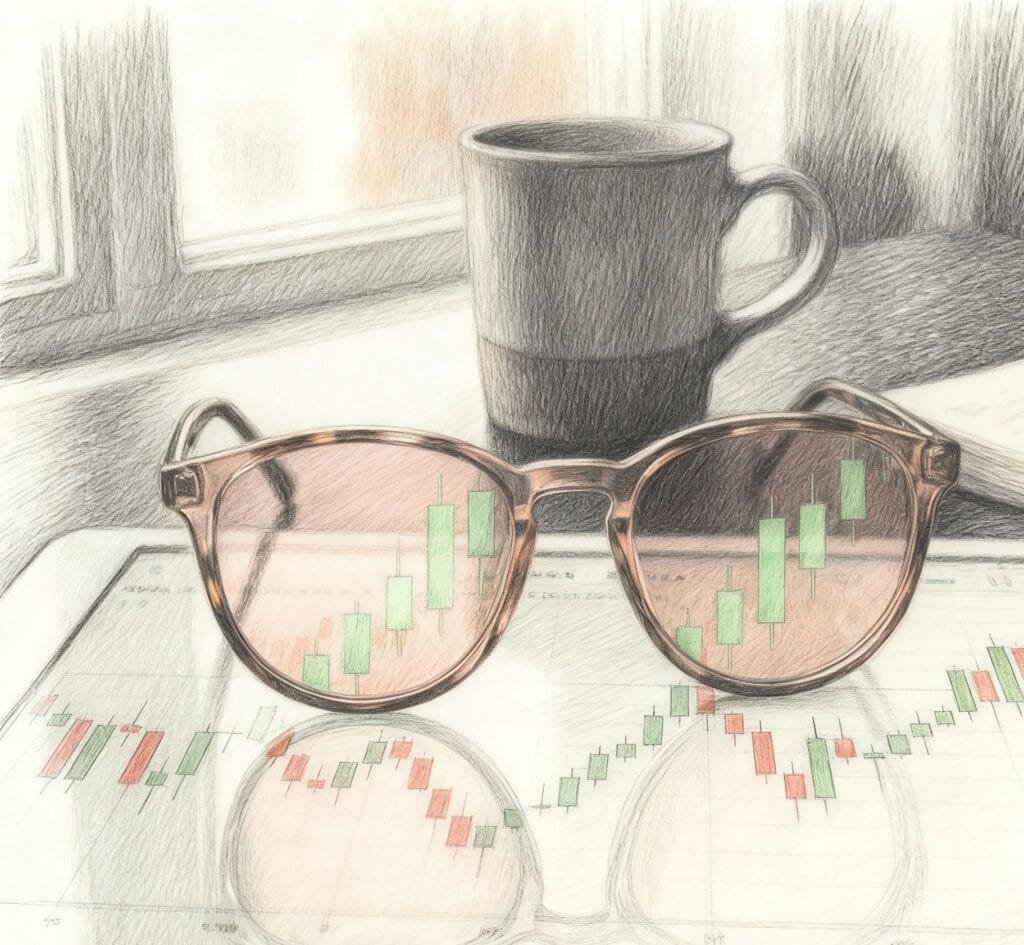

There’s something almost magical that happens the moment you buy a stock. Before you owned it, you could evaluate it coldly. You could see its flaws, question its valuation, wonder if maybe that competitor had better prospects. The stock was just another option in an infinite universe of possibilities.

Then you buy it. Suddenly everything changes.

That same stock, identical in every way to what it was five minutes ago, becomes different in your mind. It’s yours now. You didn’t just buy shares in a company. You bought a story, a future, a piece of your own judgment made manifest. The stock becomes a reflection of you.

Psychologists have a name for this. They call it the endowment effect. We value things more highly simply because we own them. Show someone a coffee mug and ask them how much they’d pay for it. They might say five dollars. Give them that same mug, let them hold it for a few minutes, then ask how much they’d sell it for. Suddenly it’s worth eight dollars. Nothing about the mug changed. Only the relationship did.

With stocks, this effect amplifies into something more profound. Because stocks aren’t just objects. They’re vessels for our hopes, our intelligence, our story about who we are and where we’re going. When you buy shares in a company, you’re not just betting on that company’s future. You’re betting on your ability to see something others missed, to be right when others are wrong, to be smarter than the market.

Your stocks become part of your identity.

When Love Becomes Blindness

The early days of ownership feel wonderful. Your stock goes up, and you feel validated. You knew it all along. You saw what others couldn’t see. Every uptick is confirmation that you’re exactly as clever as you hoped.

Then something shifts. Maybe earnings disappoint. Maybe the CEO says something concerning on a conference call. Maybe a competitor launches a better product. The stock drops. The story you bought into starts showing cracks.

This is where love turns dangerous.

A rational investor would reassess. New information demands a new evaluation. But you’re not a rational investor anymore. You’re a person whose identity is tied up in being right about this choice. So instead of reassessing, you rationalize.

The earnings miss was temporary. The CEO was taken out of context. The competitor’s product doesn’t really matter because of X, Y, and Z reasons you suddenly find compelling. You search for information that confirms your original thesis and unconsciously ignore information that contradicts it. Psychologists call this confirmation bias, but it feels more like loyalty.

You’re not being foolish. You’re being faithful.

The stock drops further. Now you’re underwater, sitting on a loss. This is where something even stranger happens. The pain of admitting you were wrong becomes greater than the pain of losing more money. Selling would mean accepting defeat. It would mean acknowledging that you got it wrong, that maybe you’re not as smart as you thought, that your judgment is fallible.

So you hold. You wait. You tell yourself stories about patience and long term thinking. Sometimes you even buy more, averaging down, doubling down on your commitment. You’re like someone in a failing relationship who proposes marriage instead of breaking up.

The Sunk Cost Trap

Here’s where things get truly irrational. You’ve already lost money. That loss exists whether you sell or hold. The money is gone. It vanished into the market’s void. What matters now is what happens next. Will this stock recover and grow? Is it still a good investment from this point forward?

But that’s not how we think. We think about what we paid. We anchor to our purchase price as if it means something to the universe. As if the market cares what you paid. As if reality has any obligation to return you to breakeven before it allows you to make a profit.

The market doesn’t know what you paid. The market doesn’t care. The only relevant question is whether the stock is worth owning at today’s price given everything you know today. Your cost basis is history. It’s emotional baggage, not financial data.

Yet we can’t let go of it. We hold losing positions because selling would make the loss real. As long as we hold, we can tell ourselves it’s just a paper loss, temporary, reversible. We can tell ourselves we haven’t really lost until we sell. This is magical thinking dressed up as strategy.

Imagine you found a stock today, never having owned it before, trading at its current price with its current prospects. Would you buy it? If the answer is no, then why are you holding it? Because you own it already? That’s not an investment thesis. That’s just inertia wrapped in emotion.

The Opposite of What You Think You Know

Here’s something counterintuitive. The stocks you should probably scrutinize most carefully are your winners, not your losers.

Everyone watches their losing positions, hoping for recovery, agonizing over whether to sell. But winners lull us into complacency. A stock that’s doubled feels like vindication. It proves you were right. This is when love really takes hold.

You start making excuses to keep holding. You tell yourself you’re letting your winners run. You remember that Buffett quote about his best decisions being the ones where he did nothing. You invoke the magic of long term compounding. These are all valid concepts, but you’re using them to justify attachment, not analysis.

The truth is more uncomfortable. Your winning stock might be overvalued now. The reasons you bought it at fifty might not apply at one hundred. The company might have changed. The competitive landscape might have shifted. But you don’t want to examine these possibilities too closely because this stock has become proof that you know what you’re doing.

It’s easier to sell a stock you’ve broken even on than one you’ve made money on. Breaking even feels like escape. Making money feels like success. But the only thing that matters is whether the stock is still worth holding at today’s price. Yesterday’s gain is as irrelevant as yesterday’s loss.

The Difference Between Conviction and Attachment

There’s a fine line between conviction and attachment. They can look identical from the outside. Both involve holding a stock through volatility. Both involve maintaining a position when others are selling. Both require ignoring short term noise.

But conviction comes from ongoing analysis. Attachment comes from emotion.

Conviction means you continually reassess your thesis against new information. You can articulate why you still hold. You can identify what would make you sell. You welcome contradictory information because it helps you refine your thinking. You’re comfortable being wrong because being right matters more than having been right.

Attachment means you’ve stopped analyzing. You hold because you’ve always held. You can’t imagine selling because selling feels like failure. You avoid information that challenges your thesis. Your reasons for holding have become vague and emotional. You’re defending a past decision rather than making a current one.

The test is simple. If someone handed you cash equal to your position’s current value, would you buy that stock today? If the answer is no, you’re attached, not convicted.

The Intimacy of Loss Aversion

Economists talk about loss aversion. We feel the pain of losses about twice as intensely as we feel the pleasure of equivalent gains. Losing a hundred dollars hurts more than gaining a hundred dollars feels good.

But this principle understates what happens with stock ownership. It’s not just that we hate losses. It’s that losses from owned positions feel personal in a way that missed opportunities don’t.

If you never bought a stock and it doubles, you feel nothing. Maybe a twinge of regret, but it’s abstract. If you bought a stock and it drops twenty percent, you feel violated. The loss is concrete, immediate, accusatory. It sits in your account, highlighted in red, reminding you of your mistake every time you check.

This asymmetry makes us irrational. We’ll take enormous risks to avoid realizing a loss while being overly cautious about taking gains. We’ll hold a losing position for years, hoping for recovery, while selling winners too early because we’re afraid of giving back profits.

The irony is perfect. The behavior that feels safe and patient is often the behavior that destroys wealth. Meanwhile, the behavior that feels reckless, selling at a loss and moving on, is often the rational choice.

When Loyalty Becomes Liability

Some investors develop relationships with companies that go beyond financial interest. They love the products. They admire the CEO. They identify with the company’s mission or culture. This can be fine. Enthusiasm has its place. But when enthusiasm becomes loyalty, you’re in dangerous territory.

Companies don’t love you back. They can’t. They’re legal fictions designed to generate returns for shareholders. When they stop generating returns, your loyalty doesn’t matter. The market doesn’t reward faithful shareholders. It rewards correct shareholders.

There’s a particular trap for people who work in an industry and invest in it. You know the space. You understand the technology or the market dynamics. This knowledge feels like an edge. Sometimes it is. But often it becomes a liability because you can’t separate your professional identity from your investment thesis.

You’re not just betting on the company. You’re betting on your expertise, your judgment within your field, your professional reputation. Admitting the investment was wrong feels like admitting you don’t understand your own industry. So you hold. You rationalize. You become defensive.

The best investors have no loyalty. They’re mercenaries, moving capital wherever the opportunity is best. This feels cold. We prefer to think of ourselves as people with values, with commitments, with loyalty. But the stock market doesn’t care about your values. It cares about value.

The Paradox of Patience

Long term investing gets praised constantly, and for good reason. Compounding requires time. Great companies need space to grow. Short term thinking destroys value.

But patience has become an excuse for stubbornness.

There’s a difference between holding a great company through temporary volatility and holding a declining company through permanent deterioration. The first is wisdom. The second is denial. But they look the same on the surface. Both involve holding. Both involve ignoring short term price movements. Both can be justified with quotes from famous investors.

The difference is in the why. Are you holding because the company’s fundamentals remain strong and the price drop is noise? Or are you holding because you can’t face the loss?

True patience requires constant vigilance. It means monitoring your positions, reassessing your thesis, staying alert to change. It means being patient about price but impatient about deteriorating fundamentals. It means being willing to hold forever if the company keeps executing, but also willing to sell immediately if the thesis breaks.

What most people call patience is actually passivity. They’re not patiently waiting for value to compound. They’re avoiding the uncomfortable work of admitting they were wrong.

Breaking the Spell

So how do you stop loving your stocks too much?

Start by recognizing that ownership changes your perception. The moment you buy something, you become biased toward it. This isn’t a flaw in your character. It’s how human psychology works. But you can compensate for it.

Make rules before you buy. Decide in advance what would make you sell. Write it down. When those conditions occur, sell. Don’t negotiate with yourself. Don’t give yourself one more quarter to see what happens. You made the rule for a reason.

Review your holdings as if you were starting fresh. Look at each position and ask if you’d buy it today. If the answer is no, you have to ask why you’re holding it. “Because I already own it” is not a reason.

Track your mistakes. Keep a journal of bad decisions. Write down what you thought and why you were wrong. This is painful. That’s the point. The pain of documentation might be less than the pain of repetition.

Talk to someone who isn’t invested. Explain your thesis. If you find yourself getting defensive or emotional, that’s a signal. Conviction welcomes scrutiny. Attachment hides from it.

Set a maximum loss you’re willing to take on any position. When it hits that level, sell automatically. No exceptions. You can decide later if you want to buy back in at a lower price. But force yourself to experience the psychological reset of selling.

The goal isn’t to become a trading machine, buying and selling without feeling. The goal is to make sure your feelings don’t override your analysis. You can care about your investments. You just can’t let caring make you stupid.

Your stocks don’t know you own them. They don’t care about your purchase price. They don’t remember your initial thesis or your reasons for believing. They just sit there, doing whatever they’re going to do, indifferent to your hopes.

You need to be equally indifferent. Not emotionless. Not uncaring. But willing to look at each position with fresh eyes, to change your mind when facts change, to admit mistakes before they compound.

The market rewards people who can think clearly about their investments. It punishes people who fall in love with them. Choose clarity over attachment. Choose analysis over emotion. Choose the future over the past.

Your portfolio will thank you. Your future self definitely will.