Table of Contents

Most investors treat the price to earnings ratio like a thermometer, checking it compulsively to diagnose market fevers. But what if you’ve been reading the wrong instrument all along? The P/E ratio tells you what the market thinks about profits, but it whispers nothing about the debt strangling those profits or the cash sitting idle in corporate vaults. Enter EV/EBITDA, the metric that forces you to think like someone buying the entire business rather than just renting a few shares.

The difference matters more than most realize. When you buy a stock, you’re technically buying a claim on future cash flows. But when you evaluate that stock using P/E alone, you’re ignoring half the story. It’s like judging a restaurant by its menu prices without checking whether it owns the building or owes the bank millions. EV/EBITDA makes you consider the whole operation, debt and all.

The Architecture of Enterprise Value

Enterprise value sounds corporate and sterile, but the concept is beautifully simple. Take the market cap, add all debt, subtract cash. You’re calculating what it would actually cost to own the entire company outright, pay off its creditors, and pocket whatever cash remains. This matters because two companies can have identical market caps but radically different enterprise values.

Imagine two coffee chains, each worth ten billion in market cap. The first is debt free with two billion in cash. The second carries three billion in debt and barely any cash reserves. To own the first outright would cost you eight billion after accounting for that cash cushion. The second would run you thirteen billion once you settle its obligations. Same stock price, wildly different realities.

EBITDA, despite sounding like a tax form, simply measures earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. Critics love to mock it as “earnings before all the bad stuff,” and they have a point. But EBITDA serves a specific purpose. It shows you the raw earning power of operations before financial engineering and accounting choices muddy the waters. A company might structure itself with mountains of debt to get tax advantages, but EBITDA strips that away to reveal the underlying business performance.

Why P/E Misleads in Predictable Ways

The P/E ratio has a fatal flaw baked into its DNA. It ignores capital structure entirely. A company can goose its earnings per share by loading up on cheap debt and buying back stock. Fewer shares outstanding means higher earnings per share, which makes the P/E look attractive. But that debt still exists, lurking in the balance sheet, waiting to cause problems when interest rates rise or revenues stumble.

Consider the leverage game that dominated corporate strategy for years. Companies borrowed heavily at low rates, used the proceeds to repurchase shares, and watched their P/E ratios compress beautifully. Investors cheered the improved metrics without asking whether the underlying business had actually improved. The enterprise value told a different story, often revealing that these financial maneuvers were expensive tricks rather than genuine value creation.

P/E also breaks down across industries in ways that make comparisons almost meaningless. Capital intensive businesses like utilities or manufacturers require constant investment in equipment that depreciates over time. This depreciation hammers reported earnings, making P/E ratios look expensive even when the business generates strong cash flow. Service businesses with minimal physical assets face no such penalty. Comparing their P/E ratios is like comparing marathon times between runners on different courses.

The Hidden Wisdom in EV/EBITDA

What makes EV/EBITDA powerful is how it levels these playing fields. By focusing on EBITDA, you sidestep the depreciation distortion that plagues P/E comparisons. By using enterprise value instead of market cap, you account for debt loads that dramatically affect what you’re really paying for.

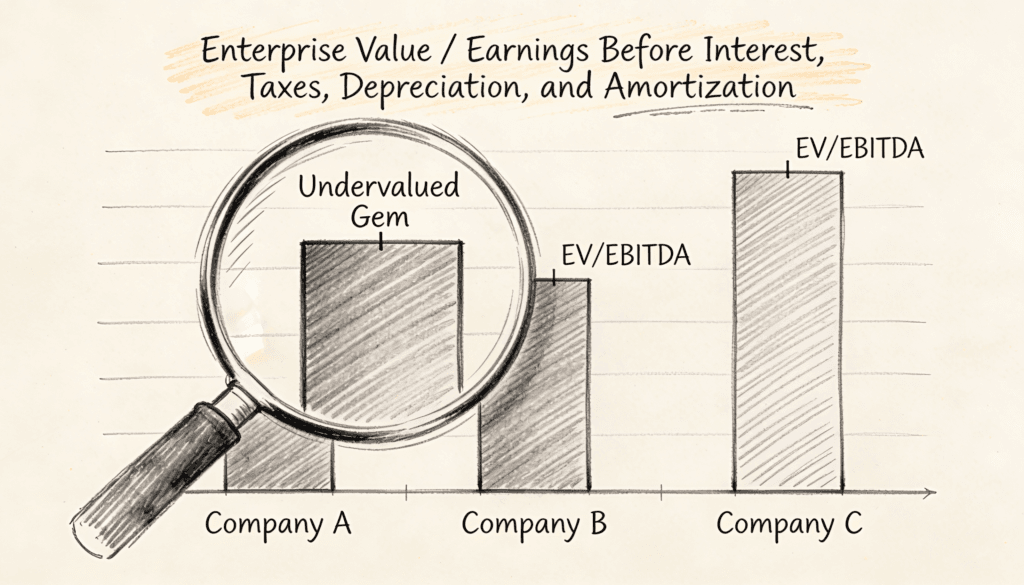

This becomes crucial when hunting for undervalued companies. A stock might look expensive on a P/E basis but reveal itself as cheap when you examine EV/EBITDA. Often this happens because the market has overlooked a strong balance sheet. A company sitting on huge cash reserves trades at a higher P/E than peers, but its enterprise value tells you that cash pile essentially gives you a discount on the operating business.

The inverse also provides valuable warnings. Companies with low P/E ratios sometimes look like bargains until you calculate enterprise value and discover mountains of debt. The apparently cheap stock becomes expensive once you realize you’re buying both the business and its crushing obligations. This happens frequently with distressed companies where the equity trades at pennies but the total enterprise value remains bloated with debt.

Reading Between the Lines

The real art lies in understanding what different EV/EBITDA levels mean across contexts. A ratio around eight to twelve represents the middle ground for most industries, though this varies wildly. Technology companies often trade at higher multiples because growth prospects justify premium valuations. Industrial businesses trade lower because they generate steady but unspectacular returns.

But averages can deceive. What matters more is spotting divergences that signal opportunity or danger. When a quality company with sustainable advantages trades at an EV/EBITDA significantly below its historical range and industry peers, you’ve found something worth investigating. The market might be overly pessimistic about temporary problems, creating an entry point for patient investors.

Look for situations where debt has scared away momentum investors but the underlying business remains sound. Sometimes companies take on leverage to fund specific projects or acquisitions. The market punishes the increased debt load indiscriminately, driving down the stock price. But if that debt finances growth that will generate returns above the cost of capital, the enterprise value becomes attractive even as the P/E ratio looks stretched.

The opposite pattern also reveals itself with regularity. Companies trading at sky high EV/EBITDA multiples despite mediocre businesses often do so because the market has fallen in love with a story. Maybe they operate in a fashionable sector or have a charismatic CEO. The enterprise value calculation forces you to confront what you’re actually paying for that story. Often the price seems absurd once you strip away the narrative.

The Psychology of Metrics

Investors gravitate toward P/E because it’s simple and everyone uses it. This creates a peculiar feedback loop. Because everyone watches P/E, corporate executives manage toward P/E. They make decisions designed to optimize this one metric, sometimes at the expense of genuine value creation. Share buybacks funded with debt make perfect sense if your only goal is compressing the P/E ratio. They make less sense if you care about enterprise value.

EV/EBITDA forces a more holistic perspective precisely because fewer investors obsess over it. Companies can’t as easily manipulate it with financial engineering. You can’t hide debt in the enterprise value calculation. You can’t make EBITDA look artificially strong without actually improving operations. This makes it harder to game but more revealing for those willing to do the work.

There’s something almost philosophical about the distinction between these metrics. P/E encourages you to think like a trader, someone who cares about share price movements and market sentiment. EV/EBITDA pushes you toward thinking like an owner, someone who cares about cash generation and balance sheet strength.

Practical Applications

Start by screening for companies where EV/EBITDA diverges meaningfully from P/E. A low EV/EBITDA coupled with a high P/E often indicates a cash rich company that the market has overlooked. These situations arise frequently with mature businesses that generate consistent profits but lack exciting growth stories. The market yawns at the boring stability, creating opportunities for value investors.

Pay special attention to companies emerging from temporary difficulties. Perhaps they’ve made a large acquisition that loaded up the balance sheet with debt, or they’re investing heavily in a new product line that’s depressing current earnings. The P/E ratio looks terrible because earnings have cratered. But if the underlying business remains strong and the debt is manageable, the EV/EBITDA might reveal a company trading well below intrinsic value.

Industry transitions create particularly fertile hunting grounds. When an entire sector falls out of favor, indiscriminate selling often pushes down prices regardless of individual company quality. Some businesses in that sector will have strong balance sheets and generate consistent EBITDA. Their enterprise values become compelling even as their P/E ratios mean nothing because earnings have temporarily vanished.

Compare EV/EBITDA ratios within industries rather than across them. A software company at fifteen times EBITDA might be cheap if peers trade at twenty five times. An industrial manufacturer at fifteen times might be expensive if the sector average is eight times. Context matters enormously. Learn the normal ranges for sectors you follow and investigate when companies deviate significantly from those norms.

The Limits of Any Single Metric

Of course, EV/EBITDA has blind spots too. EBITDA can mislead because it ignores capital expenditure requirements. Some businesses need to spend heavily just to maintain their competitive position. Those capital needs don’t show up in EBITDA, making companies look more profitable than they really are. This particularly affects industries with rapid technological change where equipment constantly needs replacement.

EBITDA also says nothing about working capital needs. Companies that must tie up cash in inventory or extend generous payment terms to customers face real costs that EBITDA ignores. Two businesses might generate identical EBITDA while one requires far more capital to sustain operations. The enterprise value accounts for debt, but it doesn’t reveal how efficiently that capital gets deployed.

The metric struggles with companies undergoing major transitions. If a business is shifting from one model to another, historical EBITDA might bear little relation to future earning power. Acquisitions can also distort the picture, especially if they involve significant restructuring costs that temporarily depress EBITDA. You need to normalize the numbers, which requires judgment and introduces subjectivity.

Combining Perspectives

The smartest approach uses multiple metrics in concert rather than relying on any single measure. Start with EV/EBITDA to identify potentially undervalued companies and account for capital structure. Then examine P/E to understand how the market views earnings quality. Look at price to book to gauge asset values. Check free cash flow to see what the business actually generates after all expenses.

Each metric provides a different lens on value. EV/EBITDA excels at comparing companies within industries and identifying capital structure opportunities. P/E captures market sentiment and earnings trends. Price to book matters more for asset heavy businesses. Free cash flow reveals the ultimate truth about value creation. Together they form a more complete picture than any single measure can provide.

Think of these metrics as witnesses in a trial. Each tells part of the story, sometimes contradicting the others, always revealing information through their particular perspective. Your job is synthesizing these testimonies into a coherent narrative about whether a business trades above or below its intrinsic worth.

The Deeper Insight

What EV/EBITDA really teaches is the importance of looking beneath surface level numbers. The stock market constantly presents you with prices, but prices mean nothing without context. A stock trading at fifty dollars per share could be expensive or cheap depending on everything else about the business. Enterprise value forces you to consider that context by making you think about total ownership costs.

This extends beyond investing into how we evaluate anything of worth. The sticker price rarely tells the complete story. A house might seem affordable until you factor in property taxes, insurance, and maintenance. A job might offer a high salary while requiring you to live somewhere expensive or sacrifice time with family. The true cost reveals itself only when you account for all the associated obligations and trade offs.

EV/EBITDA embodies this more sophisticated way of thinking about value. It refuses to let you take the easy path of just comparing price tags. It insists you consider debt, cash, and operating performance together rather than in isolation. This demands more work, but the reward is seeing opportunities that others miss because they’re content with simpler measures.

The investors who consistently outperform don’t necessarily have access to better information. They just think more carefully about what the available information actually means. They question assumptions embedded in popular metrics. They look for gaps between perception and reality. They understand that value often hides in the places everyone else has learned to ignore.

Finding undervalued gems requires training yourself to see what the market overlooks. Sometimes that means looking past scary debt levels at strong underlying businesses. Sometimes it means recognizing that cash rich companies trade at a discount to their true worth. Always it means thinking like an owner rather than a speculator, focusing on long term value rather than short term price movements.

EV/EBITDA won’t make you rich by itself. No single metric can do that. But it will make you think more clearly about what you’re buying when you purchase a stock. And in investing, clear thinking compounds over time into results that look like luck but are really just the inevitable consequence of seeing reality more accurately than the crowd.