Table of Contents

There’s a particular breed of investor who checks their brokerage account the way some people check their pulse. They want to see that dividend hit. They want confirmation that their money is working, that capital deployed is capital rewarded. And nowhere is this impulse stronger than among those who invest in business development companies.

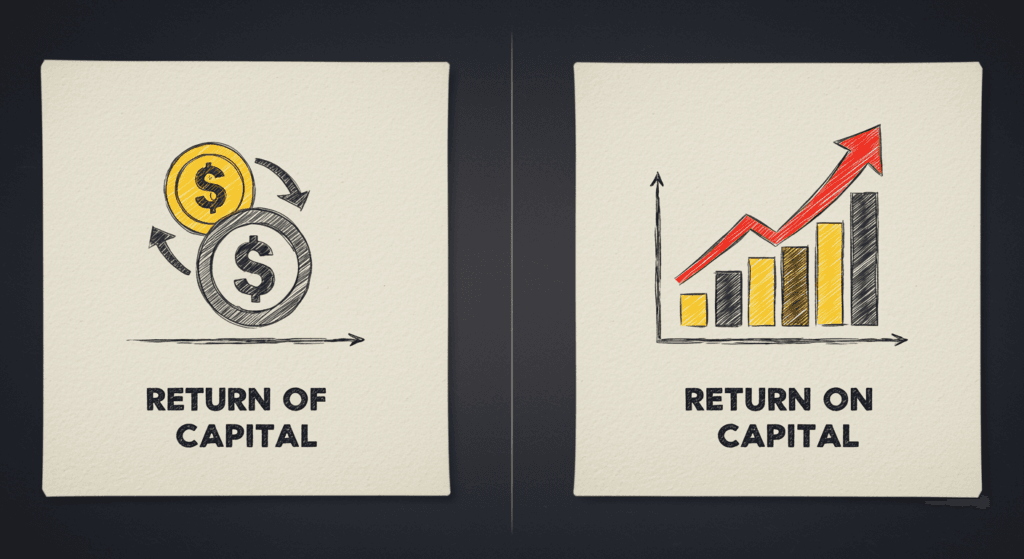

BDCs promise generous dividends, often yielding what seems like small fortunes compared to the broader market. But here’s where things get interesting. Not all dividends are created equal, and the difference between a return of capital and a return on capital is the difference between eating a meal and eating your seed corn.

The Illusion of Productivity

Think about a farmer who sells his tractor piece by piece to buy groceries. He’s generating cash flow, technically. He’s putting food on the table. But he’s not farming anymore. He’s liquidating.

This is essentially what happens when a company pays you a return of capital. They’re not handing you profits from successful operations. They’re giving you back your own money, dressed up in the costume of a dividend. It’s like lending someone twenty dollars and having them ceremoniously hand you back five while calling it interest.

A return on capital, by contrast, represents actual earnings. The company made investments, those investments generated profits, and now they’re sharing those profits with you. The machinery of capitalism worked as advertised. Your capital was put to productive use and multiplied.

The distinction seems obvious when stated plainly. Yet investors regularly miss it, seduced by the regular appearance of cash in their accounts. The payment schedule creates a rhythm that feels like progress, regardless of what’s actually happening beneath the surface.

Why BDCs Walk This Tightrope

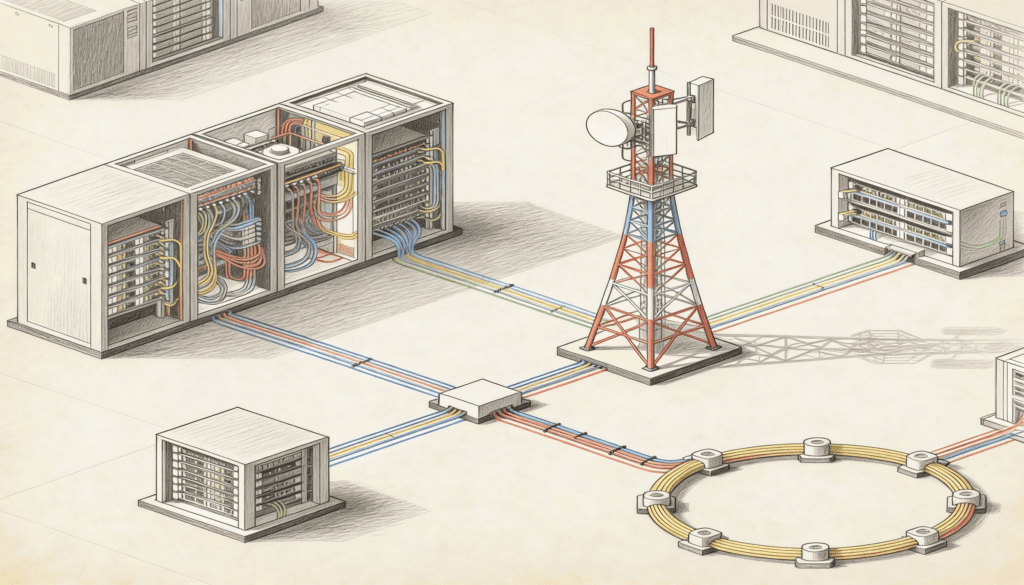

Business development companies occupy a strange space in the financial ecosystem. They’re essentially private equity funds that trade publicly, lending to middle market companies too small for traditional bank financing but too large for a simple business loan. They’re the matchmakers between capital and ambition, and their legal structure requires them to distribute substantially all of their income to shareholders.

This creates an interesting dynamic. BDCs must pay out dividends not because they’re wildly profitable, but because the tax code says so. It’s a structural requirement, not a sign of health. And when their investment income falls short of their dividend commitment, they face a choice: cut the dividend and watch shareholders flee, or maintain the dividend by returning capital.

Many choose the latter, at least temporarily. They reason that a stable dividend maintains share price, prevents panic, and buys time for investments to mature. It’s financial theater, a performance where the show must go on even when the script isn’t working.

The irony is thick here. The very mechanism designed to ensure that profits flow to shareholders can mask the absence of those profits. The mandatory dividend becomes a trap, forcing companies to signal success even in failure.

The Accounting Sleight of Hand

When you receive a return of capital distribution, your cost basis in the stock decreases. This is the paper trail of the transaction. If you bought shares at twenty dollars and received a two dollar return of capital, your cost basis drops to eighteen dollars. The tax implications differ too. You don’t pay taxes on return of capital immediately; instead, it affects your capital gains calculation when you eventually sell.

From an accounting perspective, this makes sense. You’re not being taxed on income you never actually earned. But from a psychological perspective, it creates confusion. Money arrives in your account with the same regularity as legitimate dividend income. Your brain processes it identically. The distinction exists only in the fine print of your year end tax documents.

This is where investors get into trouble. They build portfolios around dividend income without examining whether that income is sustainable or even real. They chase yields without understanding yield sources. It’s like judging a restaurant by how much food they serve without asking whether the food is any good.

The Sustainability Question

The real question investors should ask isn’t whether a dividend is a return of capital or a return on capital in any given quarter. The real question is whether the business model generates enough genuine profit to sustain distributions over time.

Some BDCs operate in this gray zone indefinitely, mixing returns of capital with returns on capital depending on how their loan portfolio performs. A few bad quarters lead to returning capital. A few good ones allow them to pay from earnings. The average investor watching their account sees only consistency, missing the underlying volatility entirely.

This creates a feedback loop. As long as the dividend checks clear, investors assume everything is fine. The BDC’s share price remains stable or grows. This allows the BDC to raise additional capital through equity offerings, which temporarily solves their cash flow problems. They use new investor money to pay existing investors, which starts to resemble something uncomfortably close to a structural problem that shall remain unnamed but involves chains and Italian surnames.

The difference, of course, is that BDCs own actual assets. They hold loans and equity positions in real companies. They’re not fabricating returns from nothing. But if those assets aren’t generating sufficient returns, then raising capital to maintain dividends is just delaying the inevitable reckoning.

What Drives Real Returns

The BDCs that consistently pay genuine returns on capital share certain characteristics. They maintain disciplined underwriting standards even when deal flow slows. They price risk accurately instead of reaching for yield. They diversify across industries and company stages. They manage their own balance sheets conservatively, avoiding excessive leverage even though their structure allows it.

These behaviors sound boring because they are boring. Sustainable profitability usually is. The exciting BDC with the twelve percent yield and aggressive growth strategy makes for better marketing copy, but marketing copy and investment thesis are different documents.

The pedestrian truth is that lending money profitably requires saying no more often than saying yes. It requires patience while competitors chase marginal deals. It requires accepting lower yields in exchange for lower risk. None of this generates headlines or excited chatter in investment forums.

Consider what happens in a strong economy. Deal flow increases, companies have options, and pricing pressure intensifies. The disciplined BDC maintains standards and watches deal volume decline. The aggressive BDC compromises on terms to maintain volume. Both pay dividends, but only one is planting seeds for the next downturn.

The Cognitive Biases at Play

Humans are pattern recognition machines, and we see patterns even where none exist. Regular dividend payments create a pattern that feels safe and predictable. Our brains interpret this regularity as evidence of underlying stability.

This is compounded by what psychologists call denomination bias. A quarterly payment of two dollars per share feels more substantial than an annual statement showing a cost basis decline of eight dollars. The cash is tangible and immediate. The cost basis is abstract and future facing.

There’s also the mental accounting trap. Investors often treat dividend income differently from capital appreciation, spending dividends while preserving principal. But if those dividends are actually return of capital, they’re spending principal while thinking they’re spending income. It’s the financial equivalent of believing you can eat your cake and have it too, when in reality you’re just eating your cake in installments.

Reading the Signs

So how do you distinguish between genuine dividend sustainability and financial theater? The answer lies in the boring work of reading financial statements and understanding business models.

Look at net investment income, not just distributions. If distributions consistently exceed net investment income, you’re likely receiving return of capital regardless of how it’s classified. Check whether the BDC is issuing new shares. Frequent equity offerings can signal that the company needs fresh capital to maintain operations, which raises questions about self sufficiency.

Examine the portfolio composition. Are loans performing? How many are on non accrual status? What’s the coverage ratio of earnings to distributions? These metrics tell you whether the machine is running smoothly or sputtering.

Also consider the incentive structure. BDC managers typically earn fees based on assets under management, creating motivation to grow even when growth doesn’t benefit shareholders. A management team that returns capital during lean times rather than chasing marginal deals is signaling something important about their priorities.

The Psychological Comfort of Dividends

There’s an interesting parallel here with the concept of consumption smoothing in economics. People prefer stable consumption patterns over time rather than feast or famine cycles. Dividend investors are essentially trying to smooth their capital consumption, taking regular distributions rather than selling shares periodically.

This makes psychological sense but creates vulnerability. The preference for smoothness can lead investors to accept artificial smoothing, where companies manufacture stable distributions through financial engineering rather than operational excellence. It’s the investment equivalent of taking out payday loans to maintain a lifestyle, sustainable only until it isn’t.

The truly counterintuitive aspect is that investors often prefer predictable mediocrity to volatile excellence. A BDC that pays a steady eight percent while slowly eroding value attracts more capital than one that pays nothing for three years then fifteen percent for two, even if the latter creates more wealth. We’re hardwired to prefer the bird in hand even when two in the bush is the better bet.

When Return of Capital Isn’t Necessarily Bad

To be fair, return of capital isn’t always problematic. Sometimes it’s part of a planned liquidation or restructuring. A BDC exiting certain investments and returning proceeds to shareholders is making a reasonable capital allocation decision. If redeployment opportunities are limited and share prices are depressed, returning capital can be shareholder friendly.

The issue arises when return of capital is chronic and unacknowledged, when it’s presented as business as usual rather than an admission that investment returns have disappointed. Context matters enormously.

Think about it this way: if you gave money to a friend to start a business and they gave you back ten percent of your capital every year while the business floundered, you’d be concerned. But if they shut down a successful venture and returned your capital with profits, you’d be satisfied. Same action, different meaning, based entirely on the surrounding circumstances.

The Path Forward for Investors

The solution isn’t to avoid BDCs or dividend paying investments generally. It’s to approach them with clear eyes and appropriate skepticism. Treat high yields as questions rather than answers. Dig into what generates those yields. Understand whether you’re being paid for risk or being paid with your own money.

Diversification helps here, but not in the traditional sense. You want diversification of dividend sources. Some portion from growth companies sharing profits, some from mature companies with stable cash flows, perhaps some from value situations where liquidation value exceeds market price. This creates resilience against any single strategy failing.

The investors who thrive long term are those who can distinguish between apparent and actual. They see through the performance to the substance. They understand that a payment isn’t a profit just because it arrives on schedule. They ask uncomfortable questions and accept uncomfortable answers.

This requires emotional discipline and intellectual honesty. It means acknowledging when you’ve made a mistake rather than rationalizing continued ownership of a deteriorating position. It means accepting lower yields in exchange for sustainability. It means sometimes being bored when others are excited and excited when others are bored.

The Ultimate Irony

Here’s the final twist: the investors most attracted to BDCs for their high dividends are often those who can least afford to have those dividends be return of capital. Retirees and others living on investment income need genuine returns, not an illusion of income created by returning their own principal in installments.

Yet these are precisely the investors most likely to overlook the distinction, focusing on the nominal yield rather than the substance. The need for income creates vulnerability to investments that promise income regardless of whether they can deliver it sustainably.

In the end, the question of whether your dividend represents a return of capital or a return on capital is really asking whether your investments are working or merely appearing to work. It’s asking whether you’re building wealth or maintaining comfortable delusions. The answer matters more than most investors realize, and ignorance here is expensive rather than blissful.

Your money should work for you. But first, you need to verify that it’s actually working.