On Market Making, Beautiful Models, and the Mess of Reality

Table of Contents

There is a particular kind of confidence that comes from solving equations on a whiteboard. It is clean. It is elegant. The variables behave themselves. The assumptions hold. And then someone walks onto a trading floor, tries to apply what they learned, and watches reality eat their model alive before lunch.

This is the story of market making, one of the most intellectually seductive corners of finance, and also one of the most humbling. It is the story of what happens when the map, no matter how beautifully drawn, meets a territory that refuses to cooperate.

The Promise of the Perfect Model

Academic finance loves elegance. The foundational models of market making are genuinely brilliant. They describe a world where a dealer sets bid and ask prices, manages inventory risk, and earns a spread that compensates them for the service of providing liquidity. The math is tight. The logic is airtight. The conclusions are satisfying.

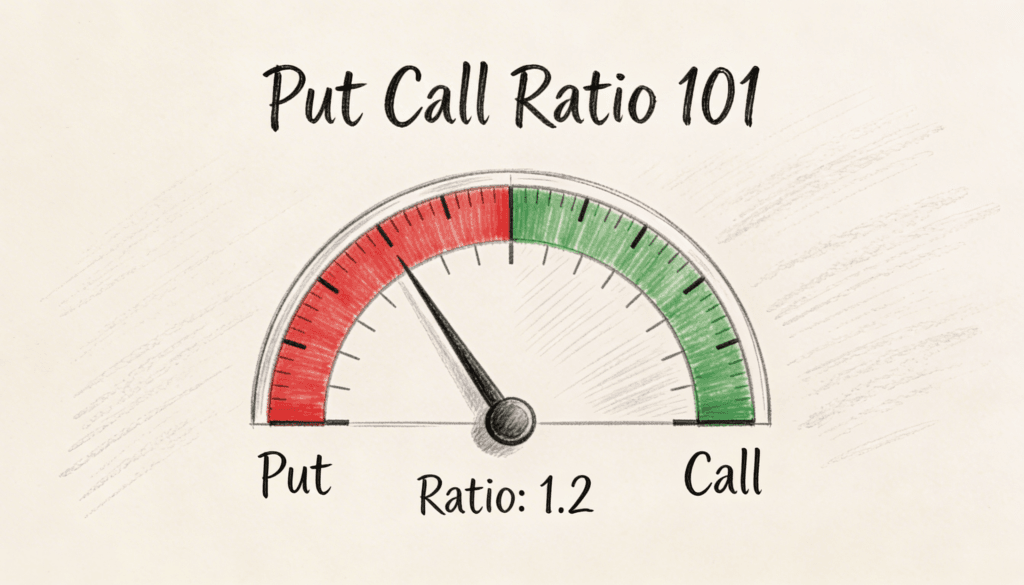

The Glosten and Milgrom model, for instance, explains the bid ask spread as compensation for the risk of trading against someone who knows more than you do. If you are a market maker and an insider comes to your desk, they will pick you off. They know the stock is about to tank, and you are the fool buying it from them. The spread exists, in theory, to offset those losses against the gains from trading with uninformed participants.

This is a wonderful insight. It explains something real. But it also assumes that the market maker can distinguish between informed and uninformed flow with some statistical clarity over time. On a real trading desk, that distinction is about as clean as a bar fight.

Then there is the Avellaneda and Stoikov framework, which treats market making as an optimization problem. The market maker adjusts quotes based on their inventory and how much risk they are willing to carry. It produces beautiful closed form solutions. It is the kind of thing that gets published in top journals and presented at conferences where everyone nods approvingly.

The problem is not that these models are wrong. The problem is that they are right in a world that does not exist.

The World the Models Forgot

Here is what academic models tend to assume, either explicitly or through convenient silence. They assume continuous markets, meaning you can always trade when you want to. They assume that prices move in well behaved increments. They assume that your orders get filled at the prices you set. They assume a single asset in isolation. They assume that other participants follow predictable patterns.

Now here is what actually happens.

Markets gap. They jump from one price to another without visiting anything in between. This is not an edge case. It is Tuesday. A headline hits, or a large order sweeps the book, or a rumor starts circulating, and suddenly your carefully placed limit orders are sitting in a world that no longer exists. The spread you thought you were earning has become a loss you are now managing.

Latency is real. In academic models, information is processed and acted on instantly. On a real trading floor, there is a gap between when information arrives and when you can respond to it. That gap might be measured in milliseconds, but milliseconds are fortunes in market making. Someone will always be faster than you. The question is not whether you get picked off. The question is how often, and whether you can survive it.

Inventory is not abstract. In theory, you manage inventory smoothly, adjusting quotes as your position grows. In practice, you can end up holding a massive position in something that has just become illiquid. The theory says to widen your spread to discourage further accumulation. Reality says there is nobody on the other side to take it from you at any price.

The Liquidity Illusion

One of the most counterintuitive lessons in market making is that liquidity is a mirage. It appears to exist in vast quantities until the moment you actually need it.

Order books look deep. You see bids and offers stacked up, suggesting that the market can absorb large trades without much price impact. But most of those orders are placed by other market makers and algorithmic traders who will pull their quotes the instant conditions change. The depth you see is conditional. It is a promise made in calm weather and withdrawn the moment a storm arrives.

This creates a strange dynamic. The more stable and liquid a market appears, the more participants rely on that appearance, and the more violent the disruption when it proves false. The flash crash of 2010, where major indices dropped and recovered within minutes, was not a failure of technology alone. It was a failure of the assumption that the liquidity visible on screen was real in any meaningful sense.

Academics call this endogenous liquidity risk. Practitioners call it getting your face ripped off.

There is a parallel here to ecology. Monoculture farming produces enormous yields under ideal conditions, but is catastrophically vulnerable to a single disease or pest. A diverse ecosystem is less efficient but far more resilient. Market making strategies built entirely on theoretical optimality are monocultures. They produce great returns until the one thing they did not model shows up. And it always shows up.

The Adverse Selection Problem Is Worse Than You Think

The theoretical models of adverse selection are surprisingly optimistic. They treat it as a manageable cost that can be priced into the spread. In practice, adverse selection is not a line item. It is an arms race.

Every market maker is trying to identify who they are trading against. Is this order from a pension fund rebalancing its portfolio, which is benign, or from a hedge fund acting on material information, which is not? The tools for making this distinction have become extraordinarily sophisticated. Firms analyze order flow patterns, correlate activity across markets, and build machine learning models to classify counterparties in real time.

But here is the catch. The informed traders know they are being classified. So they disguise their flow. They break orders into small pieces. They trade through multiple venues. They add noise. The market maker builds a better detector, the informed trader builds a better disguise, and the cycle continues. It resembles an immune system battling a constantly mutating virus. There is no stable equilibrium. There is only an ongoing contest.

This is fundamentally different from what the textbooks describe. The academic models assume a static population of informed and uninformed traders. The real world is an adaptive system where everyone is constantly adjusting their behavior in response to everyone else. Game theory captures some of this, but the actual dynamics are messier than any model can express.

When Physics Envy Becomes Dangerous

Finance has long suffered from what some call physics envy, the desire to find universal laws that govern markets the way Newton’s laws govern motion. Market making theory is a prime example. The models borrow heavily from stochastic calculus, control theory, and optimization, disciplines where the underlying systems are stable and the rules do not change.

But markets are not physical systems. They are collections of human beings making decisions based on incomplete information, shifting emotions, and constantly evolving strategies. The variables in a market making model are not like temperature or pressure. They are more like fashion trends. They change because people change, and people change because the world changes in ways that no model can anticipate.

This does not mean quantitative models are useless. Far from it. The best market makers in the world use incredibly sophisticated quantitative tools. But they use them the way a skilled sailor uses weather forecasts. The forecast informs the plan. It does not replace seamanship. When the actual weather diverges from the prediction, and it always does, you need judgment, experience, and the ability to act quickly under uncertainty.

There is a wonderful irony here. The traders who succeed are often those who understand the models deeply enough to know exactly where they break down. The theoretical knowledge is necessary, but insufficient. It is the awareness of its own limitations that makes it powerful.

The Human Element That Cannot Be Coded

Walk into a classroom and market making is a math problem. Walk onto a trading desk and it is a psychological ordeal.

Market makers must make rapid decisions under genuine uncertainty, not the sanitized uncertainty of probability distributions but the raw uncertainty of not knowing what is going on. Is this unusual activity a sign that someone knows something, or is it random noise? Is the market about to recover or is this just the beginning? There is no closed form solution for these questions. There is only judgment.

And judgment operates under pressure. Real market makers experience fear, greed, overconfidence, and panic, all the emotions that behavioral economics has cataloged but that theoretical models conveniently set aside. A market maker who has just taken a large loss will not behave like the rational agent in a textbook. They might widen their spreads too much, missing profitable opportunities. Or they might narrow them recklessly, trying to make the money back. Neither response is optimal. Both are human.

This is similar to the difference between studying chess strategy and playing a tournament. The strategy books describe ideal play. The tournament involves fatigue, time pressure, opponents who do unexpected things, and the need to manage your own mental state while calculating variations. The theory matters. But the game is played in the mind, not on the page.

Regulation and the Rules Nobody Modeled

Here is another dimension that theory tends to ignore. Market makers operate within regulatory frameworks that are complex, evolving, and occasionally contradictory. Capital requirements dictate how much risk you can carry. Reporting obligations create transparency that sophisticated players can exploit. Rules about market manipulation constrain how you can manage your book.

These are not minor details. They are structural constraints that fundamentally alter the optimization problem. A market maker who ignores capital requirements will find the optimal theoretical strategy and then discover they are not allowed to execute it. A firm that does not account for the cost of compliance will find that its elegant model produces profits on paper and losses in reality.

The Bridge Between Worlds

None of this means that academic theory is wasted. The opposite is true. The models provide the scaffolding on which practical understanding is built. You need to understand the theoretical spread decomposition before you can appreciate why it falls apart. You need to grasp the mathematics of inventory management before you can see where human judgment must override the formula.

The mistake is treating theory as the destination rather than the departure point. The ivory tower produces insights that are genuinely valuable, but they require translation. And that translation requires something that cannot be taught in a lecture hall. It requires contact with the actual market, with its noise, its randomness, its participants who have not read the same papers you have and would not care if they had.

There is something deeply instructive in this gap between theory and practice. It appears in every field where human systems are involved. Urban planning theories look beautiful until real people start living in the buildings. Military strategy is elegant until the first shot is fired. Educational theory is compelling until you stand in front of a classroom of actual students. The pattern is universal. Complex human systems resist simplification.

Market making happens to be a particularly vivid example because the feedback is immediate and measured in money. When your theory fails on a trading floor, you do not get a chance to publish a revised paper. You get a margin call.

The best practitioners in this space are those who live comfortably in the tension between theory and practice. They respect the models without worshipping them. They value intuition without trusting it blindly. They know that the map is not the territory, but they also know that wandering without a map is foolish.

The ivory tower and the trading floor need each other more than either would like to admit. The theorists provide the frameworks. The practitioners provide the reality checks. And somewhere in the ongoing conversation between these two worlds, better understanding emerges. Not perfect understanding. Never that. But better. And in a domain where the difference between a good day and a catastrophe can be measured in seconds, better is more than enough.