Table of Contents

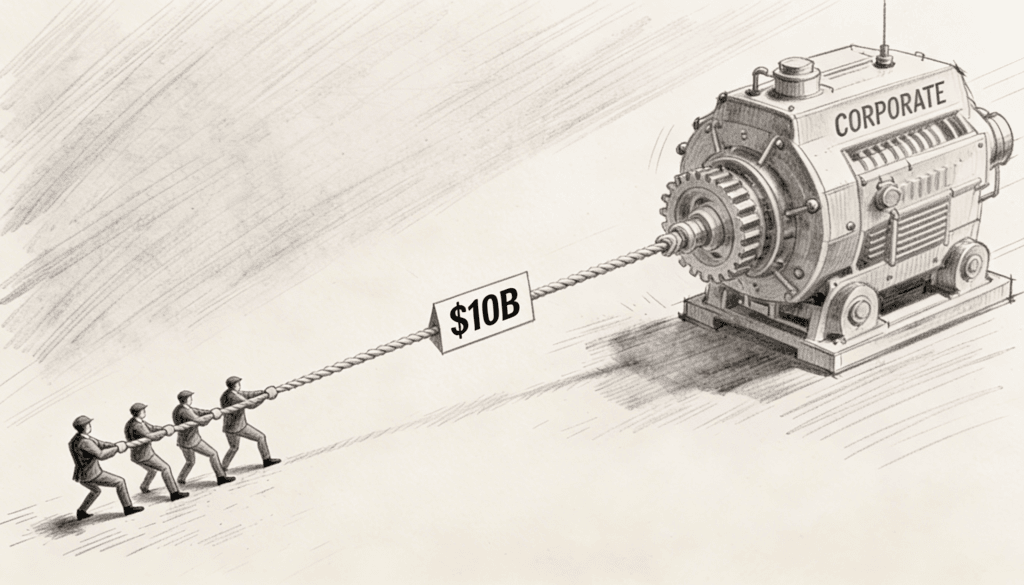

Most investors treat market capitalization like a number on a scoreboard. A company worth ten billion dollars is simply ten times bigger than one worth a billion. This arithmetic thinking makes intuitive sense until you actually try to double these companies and discover that the laws of finance behave more like the laws of physics than simple mathematics.

Think about pushing a shopping cart versus pushing a freight train. The same forward motion requires exponentially different amounts of force. Market cap works the same way, except the resistance isn’t friction but something far more complex: the constraints of reality itself.

The Gravity of Large Numbers in Physics of Finance

When a company reaches ten billion dollars in value, it has already consumed a meaningful chunk of its addressable market. This isn’t a pessimistic view. It’s geometry. Markets are finite spaces, and large objects take up more room than small ones.

Consider a software company worth a billion dollars with a hundred million in revenue. To justify its valuation, investors believe it can grow that revenue substantially. Maybe it has five percent of a ten billion dollar market. The path to doubling seems clear. Capture another five percent. The territory exists and remains largely unconquered.

Now picture that same company years later at ten billion in value with two billion in revenue. It now owns perhaps forty percent of that same market. Doubling means finding another two billion in revenue. But the map has changed. The open territory has shrunk. Competitors have claimed their stakes. The easy customers have already been converted.

This isn’t about pessimism. It’s about surface area. Small companies bump into opportunities everywhere they turn. Large companies have already absorbed the opportunities within reach. Their next moves require traveling further from home, fighting harder battles, or inventing entirely new ground to stand on.

The Energy Problem

Every billion dollars of market cap represents a stored form of energy. It’s the accumulated belief of thousands of investors, the product of years of execution, the crystallization of competitive advantages into monetary form. Adding another billion to a small company is like heating a cup of water. Adding it to a large company is like heating an ocean.

The math seems identical. One billion plus one billion equals two billion in both cases. But the systems are different sizes, and size changes everything.

A company worth a billion can double through a single breakthrough product. One killer app, one viral moment, one strategic acquisition of the right target. The energy required remains concentrated and achievable.

A ten billion dollar company needs ten of those breakthroughs to add the same multiple to its value. Or it needs one breakthrough that’s ten times larger. Both scenarios reveal the same truth: scaling isn’t linear. It’s thermodynamic.

This explains why founders often seem most energized in the early days. A small company operates near equilibrium. Changes happen fast. Decisions cascade into results within weeks. A large company operates far from equilibrium. It has momentum, yes, but momentum becomes inertia at scale. Changing direction requires enormous applied force over sustained periods.

The Observer Effect

Here’s where finance truly mirrors physics: the act of observation changes the thing being observed.

When a company is small, it can move quietly through markets. It can test products in obscurity. It can pivot without scrutiny. It operates below the resolution of most radars.

When a company is large, every move is watched. Competitors study its patents. Regulators monitor its growth. The media analyzes its quarterly calls. This observation doesn’t just record reality. It constrains it.

A billion dollar company can enter a new market and surprise everyone. A ten billion dollar company telegraphs its intentions through hiring patterns, acquisition rumors, and strategic announcements. By the time it makes a move, the market has already reacted. Competitors have erected defenses. Customers have set expectations. The element of surprise, that most valuable of strategic assets, has evaporated.

This creates a paradox. The larger the company, the more resources it has to deploy. But the larger the company, the harder it becomes to deploy those resources effectively. It’s like trying to surprise someone while wearing a bell around your neck. The sound travels faster than you can move.

Network Effects in Reverse

We love talking about network effects when they work in a company’s favor. Each new user makes the product more valuable for existing users. Growth bring more growth in a virtuous cycle.

But network effects have a dark mirror that emerges at scale. Call them network constraints. As a platform grows, it must serve increasingly diverse and conflicting user needs. The product that delighted early adopters starts making compromises to accommodate mainstream users. The culture that moved fast and broke things must now move carefully to avoid breaking millions of things for millions of people.

A social network at a billion dollar valuation can afford to be edgy. It can take risks with its interface. It can experiment with controversial features. Its small user base provides permission for boldness.

That same network at ten billion must navigate the politics of nations. It must balance free speech against safety, personalization against privacy, engagement against mental health. Every decision disappoints someone. Often it disappoints millions of someones. The cost of experimentation scales with the number of people affected.

This isn’t about weak leadership or bureaucratic bloat. It’s about operating at a scale where your actions have genuine geopolitical implications. At that point, you’re not just building a product. You’re governing a digital polity. And governance requires different tools than growth hacking.

The Talent Magnet Problem

Small companies attract people who want to build something from nothing. They offer equity that could 10x. They provide wide responsibility and steep learning curves. They promise the thrill of watching your individual contributions move the needle.

Large companies attract people who want stability, prestige, and competitive salaries. They might offer equity that might double over five years. They provide deep specialization and clear career ladders. They promise the security of working on proven business models.

Neither set of motivations is superior. But they are different. And the difference matters when you’re trying to double a company.

Doubling from one to two billion requires missionary zeal. You need people who believe despite limited evidence. Who work through uncertainty because the potential reward justifies the risk. Who derive energy from the possibility of creating something unprecedented.

Doubling from ten to twenty billion requires operational excellence. You need people who optimize existing systems. Who find two percent improvements across a thousand processes. Who derive satisfaction from making a giant machine run more smoothly.

The skills don’t transfer cleanly. A brilliant startup generalist often struggles in a specialized role at a large company. A talented corporate operator often flounders in the chaos of a startup. This means that as companies grow, they must constantly reinvent their talent base. The people who got them to ten billion are often not the people who can get them to twenty.

This isn’t a failure of the people. It’s a mismatch of the mode. You can’t blame a sprinter for struggling with a marathon. The race has changed shape.

The Denominator of Expectations

Here’s a subtle effect that punishes scale: percentage movements feel smaller on large numbers even when absolute changes are identical.

A billion dollar company that gains a hundred million in value has grown ten percent. Headlines celebrate. Investors cheer. Employees feel momentum.

A ten billion dollar company that gains a hundred million has grown one percent. The news barely registers. Investors shrug. Employees wonder if they’re stagnating.

Same absolute gain. Wildly different psychological impact.

This matters because markets are made of humans and humans run on feeling as much as logic. A company growing at fifty percent annually feels electric even if it’s adding modest absolute value. A company growing at ten percent annually feels sluggish even if it’s adding billions.

The emotional energy available to a company is partly a function of its perceived velocity. And velocity is measured in percentages, not dollars. This means that as companies grow, they must generate increasingly massive absolute gains just to maintain the feeling of momentum. The treadmill speeds up while the scenery changes more slowly.

The Optionality Tax

Small companies exist in a fog of possibilities. They could become anything. Maybe they’ll dominate enterprise software. Maybe they’ll pivot to consumer apps. Maybe they’ll get acquired by a tech giant. This ambiguity is valuable.

Investors price in multiple potential futures. The stock reflects not just the current business but the option value of unexplored paths. It’s like holding a lottery ticket where you haven’t checked all the numbers yet. Hope trades at a premium.

Large companies have revealed themselves. Their strategy is public. Their market position is clear. Their growth vectors are mapped. The fog has lifted and with it, much of the option value.

This doesn’t mean large companies lack potential. But it means their potential is more defined and therefore more constrained by probability. Investors can calculate the realistic boundaries of future performance. The lottery ticket has been checked. You know what you have.

Going from one billion to two means executing on still-vague promises. Going from ten billion to twenty means delivering specific, quantifiable results in well-defined markets. The former leaves room for imagination. The latter demands demonstration.

Why This Matters Beyond Finance

Understanding these dynamics changes how we think about ambition, timing, and career choices. The best moment to join a rocketship isn’t always at launch. Sometimes it’s after the initial boost but before maximum altitude, when momentum remains strong but before operational complexity becomes overwhelming.

It also reveals why some founders struggle after their first success. The skills that take a company from zero to a billion are genuinely different from those that take it from ten to twenty billion. Neither set is superior. But recognizing the difference allows for better planning and more honest self-assessment.

For investors, this framework explains why diversification across company sizes makes sense beyond simple risk management. Small companies offer asymmetric upside but high failure rates. Large companies offer steady compounding but limited multiples. The efficient portfolio isn’t one or the other but a thoughtful mix calibrated to goals and timeline.

The Escape Velocity Question

Some companies do break through these constraints. They find ways to double and double again even at massive scale. Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft have demonstrated that scale doesn’t automatically mean stagnation.

But look closely at how they’ve done it. They don’t double their core business. They add new businesses. Amazon moved from books to everything, then to cloud computing, then to advertising. Apple moved from computers to phones to services. Microsoft moved from software to cloud to gaming.

They achieved escape velocity not by pushing harder on the same trajectory but by finding new trajectories entirely. Each new business line resets the clock. Each provides fresh room to grow before hitting the natural constraints of its market.

This is the only reliable pattern for doubling at scale: become a portfolio of businesses rather than a single company. But this strategy carries its own costs. Complexity increases. Culture dilutes. The original mission that united everyone becomes one mission among many.

The Humility of Scale

Perhaps the deepest insight from this physical view of finance is that growth at scale requires humility. When doubling meant adding a hundred million in value, bold vision and fierce execution were sufficient. When doubling means adding ten billion, you need something else: the wisdom to recognize what you cannot control.

Large companies grow not just through their own efforts but through tides in the broader economy, shifts in technology platforms, changes in regulation, and luck. The larger you are, the more your fate intertwines with forces beyond your influence.

This doesn’t mean leaders of large companies are passive. But it means their role shifts from pure creation to navigation. From imposing will upon reality to reading reality and responding with nuance. From moving fast and breaking things to moving deliberately and building things that last.

The physics of finance teaches us that size changes everything. Not just the numbers, but the nature of the game itself. Understanding this helps us appreciate why the companies that successfully scale are so rare. They’ve done something that gets exponentially harder with each increment of success.

The next time you see a ten billion dollar company double in value, don’t just note the achievement. Marvel at the physics defying nature of what just occurred. Because in the world of scale, doubling isn’t arithmetic. It’s a kind of magic, made possible only by understanding and working with the invisible forces that govern growth itself.