Table of Contents

There’s a peculiar ritual that plays out in conference rooms across the financial world. An analyst presents a valuation model, and somewhere in the deck sits a page titled “Comparable Company Analysis.” The companies listed there read like a guest list to an exclusive party: Apple, Google, Microsoft. Everyone nods. The analysis feels solid, defensible, scientific even.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth. We didn’t choose these comparables because they were the most similar to our target company. We chose them because we’ve heard of them. Because they feel important. Because citing Apple in our analysis makes us feel like serious people doing serious work.

This is the prestige bias at work in finance, and it quietly undermines one of the most fundamental tools in our valuation toolkit.

The Comfort of the Familiar

Comparable company analysis rests on a simple premise. Find companies that look like yours, see what the market values them at, and use that as a benchmark. In theory, it’s elegant. In practice, we keep reaching for the same handful of names because they exist in our mental space.

The problem isn’t that these prestigious companies are bad businesses. They’re usually exceptional. The problem is that exceptional isn’t the same as comparable. When you’re valuing a regional software company with $50 million in revenue, using Microsoft as a comparable says more about your desire for credibility than your commitment to accuracy.

This tendency connects to something deeper in human psychology. We trust what we recognize. The mere exposure effect, documented across decades of research, shows that familiarity breeds affection and perceived competence. We assume the company we’ve heard of a thousand times must be more relevant than the one we discovered through careful screening.

In finance, this instinct becomes dangerous. The whole point of comparable company analysis is to find true peers, companies facing similar markets, growth trajectories, and operational challenges. But we’re not wired to think this way. We’re wired to think in terms of categories and hierarchies. Tech company? Must be like Apple. Retailer? Must be like Amazon.

The Illusion of Sophistication

There’s a theater to financial analysis. We perform credibility for our audience, whether that’s a boss, a client, or a committee. And nothing performs credibility quite like dropping a prestigious name.

Say you’re analyzing a small athletic apparel company. You could spend hours researching niche competitors with similar distribution models and margin profiles. Or you could put Nike in your comp set and watch heads nod approvingly around the table. One approach is rigorous. The other is recognizable.

The recognizable wins more often than we’d like to admit.

This creates a curious inversion. The more prestigious the company in your comp set, the less useful it often is. Nike has global scale, unmatched brand equity, and supply chain advantages that took decades to build. Using it to value a startup selling yoga pants online is like using a cruise ship to estimate the price of a kayak. They both float, technically.

Yet the inclusion of Nike makes the analysis feel substantial. It suggests we’ve done our homework, that we understand the industry, that we’re thinking at the right altitude. The irony is that the homework we’re supposed to have done is finding actual comparables, not collecting trophy names.

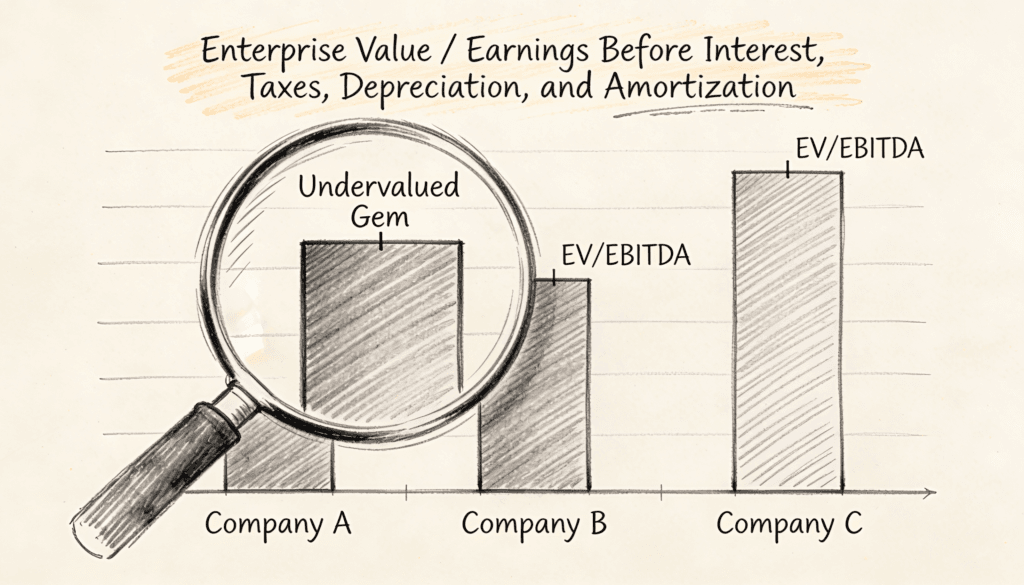

When Prestige Becomes Proxy

The deeper issue is that prestige starts to substitute for the characteristics we actually care about. We know we should be matching on metrics like growth rate, margin profile, market position, and business model. But these require judgment calls and deep dives into company filings. Prestige is immediate and unambiguous.

This is how Goldman Sachs ends up in every financial services comp set, regardless of whether you’re valuing a multinational investment bank or a regional wealth management firm. Goldman is finance. Using Goldman signals that you understand what finance is. Never mind that its revenue mix, capital structure, and regulatory environment might bear little resemblance to your target.

The substitution happens unconsciously. We tell ourselves we’re being thorough by including industry leaders. We’re not ignoring the smaller, truer peers. We’re just adding perspective. But that perspective has weight. When you average multiples, the prestigious outlier pulls your entire valuation in its direction.

Consider what happens in practice. You find five true peers, companies with remarkably similar profiles to your target. Then you add two industry giants for “context.” Suddenly your valuation range stretches to accommodate these giants. The midpoint shifts. And you find yourself defending a number that has more to do with Microsoft’s multiple than with the actual company you’re trying to value.

The Consensus Trap

Prestige bias feeds on itself through a mechanism economists call information cascades. One analyst includes a prestigious name in their comp set. Others see it and think, “They must know something I don’t.” Soon, everyone is using the same big names, not because they’re appropriate, but because everyone else is using them.

This creates a false sense of validation. If every analyst covering the retail sector includes Amazon in their comp sets, it starts to feel like a methodologically sound choice rather than a collective oversight. The consensus becomes self-reinforcing, resistant to challenge.

There’s safety in this consensus. If your valuation is wrong but you used the same comparables as everyone else, you’re not really wrong. You’re just part of a group that was wrong, which in professional terms is vastly preferable to being wrong alone. The institutional pressure to avoid standing out often overwhelms the analytical pressure to be precise.

This is where finance reveals itself to be as much about social dynamics as mathematics. We like to think we’re evaluating cash flows and risk premiums with cold rationality. But we’re also watching what our peers do, seeking approval from authority figures, and protecting our reputations. The prestigious comparable serves all these social needs while nominally serving an analytical one.

The Complexity Shield

Prestigious companies often have another advantage in comp sets. They’re complicated. Conglomerates with multiple business lines, international operations spanning dozens of countries, revenue streams that blur across categories. This complexity can actually work in favor of their inclusion.

When someone questions why you’ve included a massive, diversified company as a comparable for a focused, single product business, you can gesture toward some small division that kind of, sort of overlaps. “Well, they do have that emerging markets segment that’s actually quite similar to what we’re looking at.” The complexity provides cover.

Simpler, more directly comparable companies offer no such refuge. Their relevance is obvious or it isn’t. There’s nowhere to hide. So we gravitate toward the complex and prestigious, where we can always find some thread of connection if pressed.

This inverts the principle of Occam’s Razor in a peculiar way. In science, we prefer simpler explanations. In comp selection, we prefer more complicated companies because their complexity gives us flexibility to justify their inclusion after the fact.

Breaking the Pattern

Recognizing prestige bias is easier than overcoming it. The pull is strong, the incentives are real, and the social costs of deviation are tangible. But there are practices that help.

Start by forcing yourself to articulate why each comparable is comparable before you look at any valuation multiples. Write down the specific characteristics that make two companies peers. Revenue size, growth rate, margin profile, geographic mix, customer concentration, competitive position. If you can’t list at least five meaningful similarities, you probably don’t have a true comparable.

This exercise reveals how often we’re working backward. We pick companies, then rationalize their inclusion. Forcing the justification upfront disrupts this pattern.

Second, impose a recognition penalty. If a company is well known enough that your parents have heard of it, it probably shouldn’t be in your comp set unless you’re valuing another company your parents have heard of. Obvious exceptions exist, but the heuristic surfaces how often prestige is driving selection.

Third, embrace the awkward moment when someone asks why you didn’t include the obvious industry giant. This question will come. Prepare for it. “I excluded them because while they’re in the same broad industry, their scale, market position, and business model differ materially from our target in these specific ways.”

The key is demonstrating that you considered and rejected the prestigious name for analytical reasons, not because you were unaware of it. You’re not missing the elephant in the room. You’re consciously deciding the elephant isn’t a useful point of comparison.

What True Comparability Looks Like

Finding genuine peers requires patient work. It means reading industry reports, following footnote references in 10-Ks, attending trade conferences, and building knowledge of the ecosystem beyond the handful of names that make headlines.

Often, the best comparables are private companies or foreign firms that don’t trade on major exchanges. They’re harder to research, their data is less accessible, and you can’t just pull their multiples from a Bloomberg terminal. But they’re actually similar to your target in ways that matter.

This is where analyst skill truly shows. Anyone can pull up a screen for large cap tech companies. It takes judgment and effort to identify that the right comparable for your European logistics company is actually a Brazilian firm with a similar last mile strategy, even though they operate in different geographies.

The prestige bias is ultimately a failure of intellectual courage. We choose comfort and consensus over accuracy. We opt for the analysis that’s easy to defend rather than the analysis that’s most likely to be right. And we do this while telling ourselves we’re being rigorous.

The Broader Lesson

This pattern extends beyond comparable company analysis. Throughout finance, we overweight information and institutions that feel important while underweighting information and institutions that would actually be more useful.

We pay more attention to Federal Reserve announcements than to changes in bank lending standards, even though the latter might be more predictive of economic activity. We obsess over what large hedge funds are buying while ignoring the aggregate behavior of smaller investors. We quote famous investors and economists, whether or not their expertise is relevant to the question at hand.

In each case, prestige substitutes for relevance. The recognizable becomes a proxy for the reliable. And we end up with analysis that sounds sophisticated but rests on a foundation of name recognition rather than genuine similarity.

The solution isn’t to ignore prestigious companies entirely. Sometimes they genuinely are the best comparables. Sometimes their scale and success provide useful context even when they’re not perfect peers. The solution is to be honest about why we’re including them and to resist the gravitational pull they exert on our thinking.

Finance pretends to be purely quantitative, a realm of spreadsheets and models where bias has no place. But every number in those spreadsheets came from a choice someone made. Which companies to compare. Which metrics to emphasize. Which outliers to exclude. And those choices are made by human beings subject to all the usual human tendencies.

The prestige bias is just one of many ways our intuitions lead us astray. We’re not being lazy. We’re including the industry leaders! What could be more diligent than that?

The answer, of course, is finding the companies that actually look like the one we’re trying to value, even if no one in the room has heard of them. Even if their inclusion doesn’t make our analysis feel impressive. Even if it means more work and less validation.

That’s what rigor actually looks like. Not a comp set full of household names, but a comp set full of genuine peers, chosen for their similarity rather than their fame. The next time you’re tempted to throw Apple into your analysis because it makes everything feel more substantial, pause. Ask whether you’re seeking truth or seeking credibility. Usually, you can’t optimize for both.