Table of Contents

The Problem with Labels

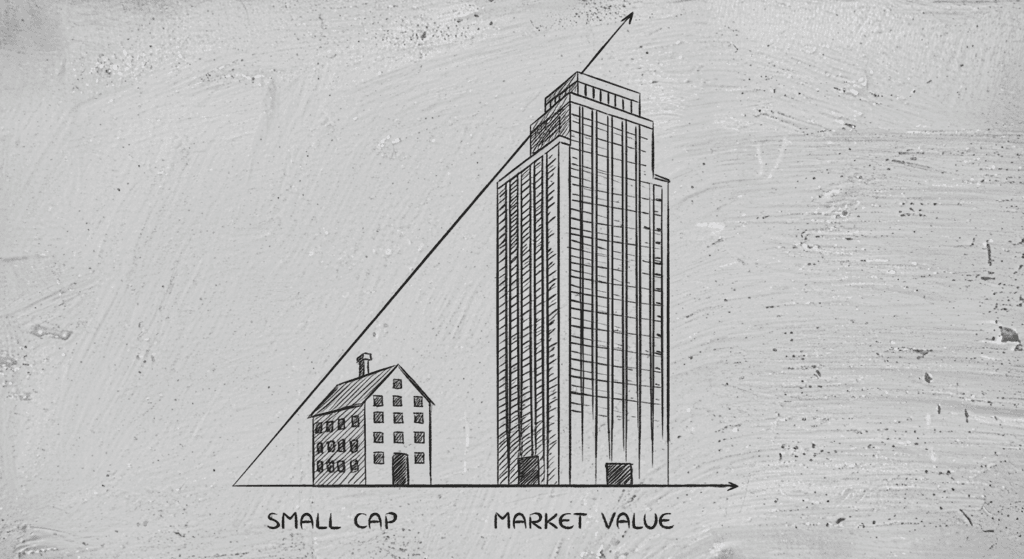

Language shapes reality in peculiar ways. We call certain stocks “small cap” and assume we’re talking about small companies. But language is a lazy shorthand, and finance is full of shortcuts that stop making sense the moment you look closer.

The market capitalization of a company tells you what investors think the equity is worth. Nothing more, nothing less. A company with a market cap of two billion dollars sits in the small cap category by most definitions. Yet that same company might employ fifteen thousand people, operate in forty countries, and generate three billion in annual revenue. Small in one dimension, substantial in others.

This matters because investors make decisions based on mental models. When you hear “small cap,” your brain likely conjures an image of a scrappy startup, a garage operation scaling up, a company still finding its footing. Sometimes that’s accurate. Often it’s not.

When Old Companies Look Small

Consider a family owned business that’s been around for seventy years. The founding family retains eighty percent of the shares and has no interest in selling. Only twenty percent trades publicly. The float is thin, so the market cap stays modest even though the enterprise value might be enormous. By market cap standards, it’s small. By every other measure, it’s an established player with deep roots and institutional memory.

The reverse happens too. A newly public tech company with negligible revenue but soaring investor enthusiasm might sport a market cap that places it firmly in mid cap or even large cap territory. The company is objectively small by headcount, by sales, by market presence. But the stock price reflects future expectations rather than present reality, inflating the market cap beyond what current fundamentals would suggest.

This disconnect between label and substance isn’t just semantic. It affects how we think about risk, growth potential, and competitive positioning. The “small cap” label carries connotations that may not apply to the actual business beneath the ticker symbol.

How Labels Become Self Fulfilling

Think about it through the lens of perception versus reality, a theme that runs through everything from quantum physics to social psychology. In physics, the observer affects the observed. In finance, the classification affects the classified. Once a stock gets labeled small cap, it attracts a certain type of investor, gets included in certain indices, faces certain regulatory requirements, and trades with certain liquidity characteristics. The label becomes self reinforcing.

Small cap indices exclude stocks below a certain market cap threshold and above another. A company growing its market cap might graduate out of small cap indices, forcing passive funds to sell regardless of the underlying business quality. A company whose stock price falls might get demoted into small cap indices, forcing purchases from funds that track those benchmarks. These mechanical flows have nothing to do with whether the company itself is genuinely small or large in operational terms.

The Geography Problem

The confusion deepens when you consider international comparisons. A company with a five billion dollar market cap might be considered mid cap in the United States but large cap in a smaller economy. The same business, the same operations, different labels depending on the pond you’re measuring it against. Geography shouldn’t change the fundamental nature of an enterprise, yet the classification system makes it seem like it does.

Market cap also fluctuates with investor sentiment in ways that revenue, assets, and employee count do not. A company can be small cap one quarter and mid cap the next without changing anything about its operations. The business didn’t transform. The stock price moved. Yet the label shifts, and with it the assumptions investors make.

Useful Fictions and Misleading Truths

There’s an irony here that’s worth sitting with. We created market cap categories to make sense of the investment universe, to create buckets that help us compare and analyze. But the buckets themselves introduce distortions. They’re useful fictions that occasionally become misleading truths.

Some genuinely small companies have large market caps because investors believe in explosive growth ahead. Some genuinely large companies have small market caps because they operate in unglamorous industries or because their capital structure limits the publicly traded float. The map is not the territory, but we keep navigating by the map and forgetting to look out the window.

This dynamic parallels how we categorize in other domains. We call certain countries “developing” based on GDP per capita, even when they have ancient civilizations, sophisticated cultural institutions, and infrastructure that puts wealthier nations to shame in specific areas. The economic metric becomes a stand in for a much more complex reality. We do the same thing with market cap and company size.

What This Means for Your Portfolio

The practical implications matter for portfolio construction. If you’re allocating to small caps because you want exposure to young, high growth businesses with entrepreneurial energy, you might be surprised to find your small cap fund filled with mature in terms of age, slow growing companies that just happen to have modest market caps. The opposite applies if you think you’re avoiding small cap risk by sticking to larger market caps, only to discover you own recent IPOs with limited operating history.

Valuation metrics add another layer of confusion. A company trading at a low price to earnings ratio seems cheap, but if it’s small cap, conventional wisdom says it should trade at a discount to larger peers because of higher risk and lower liquidity. Except sometimes the small cap label is misleading about actual risk, and the discount is unwarranted. Other times a small cap trades at a premium because it’s genuinely a fast growing small company, not just a company with a small market cap.

The Venture Capital Contrast

The venture capital world offers an interesting contrast. VCs invest in companies that are truly small, often with minimal revenue and tiny teams. They’re not confused about company size because there’s no stock price to create false signals. The company is worth what someone will pay for it in a negotiated transaction, not what a public market implies through continuous trading. Once these companies go public, the market cap mechanism takes over, and the potential for label mismatch emerges.

The Abstraction Problem

This gets at something deeper about how financial markets create abstractions that take on lives of their own. Market cap is an abstraction, a mathematical product of share price and share count. It’s useful for certain purposes, like determining index weights or liquidity metrics. But it’s a terrible proxy for company size in any holistic sense.

Company size is multidimensional. It includes revenue, assets, employees, market reach, brand recognition, political influence, and cultural footprint. Market cap captures exactly one thing, the current collective guess about what the equity is worth. Collapsing all those dimensions into a single metric inevitably loses information.

Yet we persist in using market cap categories as if they tell us everything we need to know. It’s cognitively efficient, which is why the practice endures. Our brains like shortcuts. The financial industry likes standardization. So we get small, mid, and large cap as organizing principles despite their limitations.

What Makes Something Small?

The philosophical question underneath all this is about what makes something small or large. Is size an intrinsic property or a relative one? A mouse is small compared to an elephant but large compared to an ant. Context determines the answer. In finance, the context is supposedly the market, but the market is measuring something specific that doesn’t necessarily correlate with size in other dimensions that matter.

There’s also a temporal element. A company that was large cap five years ago might be small cap today not because it shrunk but because it grew slower than its peers or because investor enthusiasm waned. The company might be larger in absolute terms, more employees, more revenue, more global presence. But the stock underperformed, so it’s now “small.” The backward looking nature of classification creates odd situations where growth equals demotion.

The Heap Paradox

This reminds me of the Sorites paradox, the ancient puzzle about heaps. If you have a heap of sand and remove one grain, you still have a heap. Keep removing grains one at a time, and at some point it stops being a heap, but there’s no clear boundary. When exactly does a large cap become a mid cap? The thresholds are arbitrary, yet we treat them as meaningful.

The investment industry has built entire strategies around these categories. Small cap value funds, large cap growth funds, mid cap blend funds. Each slice gets its own products, its own academic research, its own performance benchmarks. The infrastructure assumes the categories are real and stable, even though they’re fluid and somewhat arbitrary.

How Categories Affect Decisions

Behavioral finance teaches us that categories affect decision making. Once you label something, you activate certain mental heuristics. Small cap activates thoughts about risk, volatility, growth potential, and limited analyst coverage. Those associations influence how you evaluate the investment, sometimes appropriately, sometimes not. If the company isn’t actually small in meaningful ways, the heuristic leads you astray.

There’s a hidden assumption in all this that equity market cap should be the primary way we think about company size. But why? Revenue is more stable. Employee count is harder to manipulate. Total assets reflect accumulated resources. Any of these could serve as the basis for categorization. We settled on market cap largely because it’s convenient for index construction and because it reflects investor consensus about value. Convenience and consensus aren’t the same as correctness.

When Smart Money Exploits the Gap

Activist investors sometimes exploit these disconnects. They identify companies with small market caps relative to their asset base or earning power, accumulate shares, and push for changes that unlock value. The market cap was small, but the opportunity was large. The label masked the reality until someone looked beneath the surface.

Private equity firms do something similar. They take public companies private, often at premiums to the prevailing market cap, because they see value that public markets are missing. The company doesn’t change fundamentally when it goes private, but the market cap disappears. Without that label, different possibilities emerge.

The Core Insight

This might be the core insight. Market cap is an artifact of public trading, not an intrinsic feature of a business. It’s the residue of collective buying and selling, useful for certain purposes, misleading for others. Treating it as synonymous with company size is like treating a person’s social media follower count as synonymous with their actual influence or importance. There’s correlation sometimes, but the exceptions are numerous and important.

What Investors Should Do

For individual investors, the lesson is to look past labels. Don’t assume small cap means small company or that large cap means large company. Check the fundamentals. Look at revenue, assets, employees, competitive position, and market structure. The market cap will tell you what the stock market thinks the equity is worth today. It won’t tell you whether the company is genuinely small or large in ways that matter for your investment thesis.

Language matters because it shapes thought. If we keep calling stocks small cap when the underlying companies aren’t particularly small, we’ll keep making errors that flow from that mismatch. Better language might lead to better thinking, which might lead to better investing.

The financial markets are full of these useful fictions that outlive their usefulness or get applied beyond their proper scope. Market cap categories serve a purpose and recognizing the gap between label and reality is the first step toward navigating it more skillfully.

In the end, small cap doesn’t always mean small company because we’re measuring different things and pretending we’re not. The sooner we acknowledge that openly, the clearer our thinking will become. The map will still not be the territory, but at least we’ll remember to distinguish between them.