Table of Contents

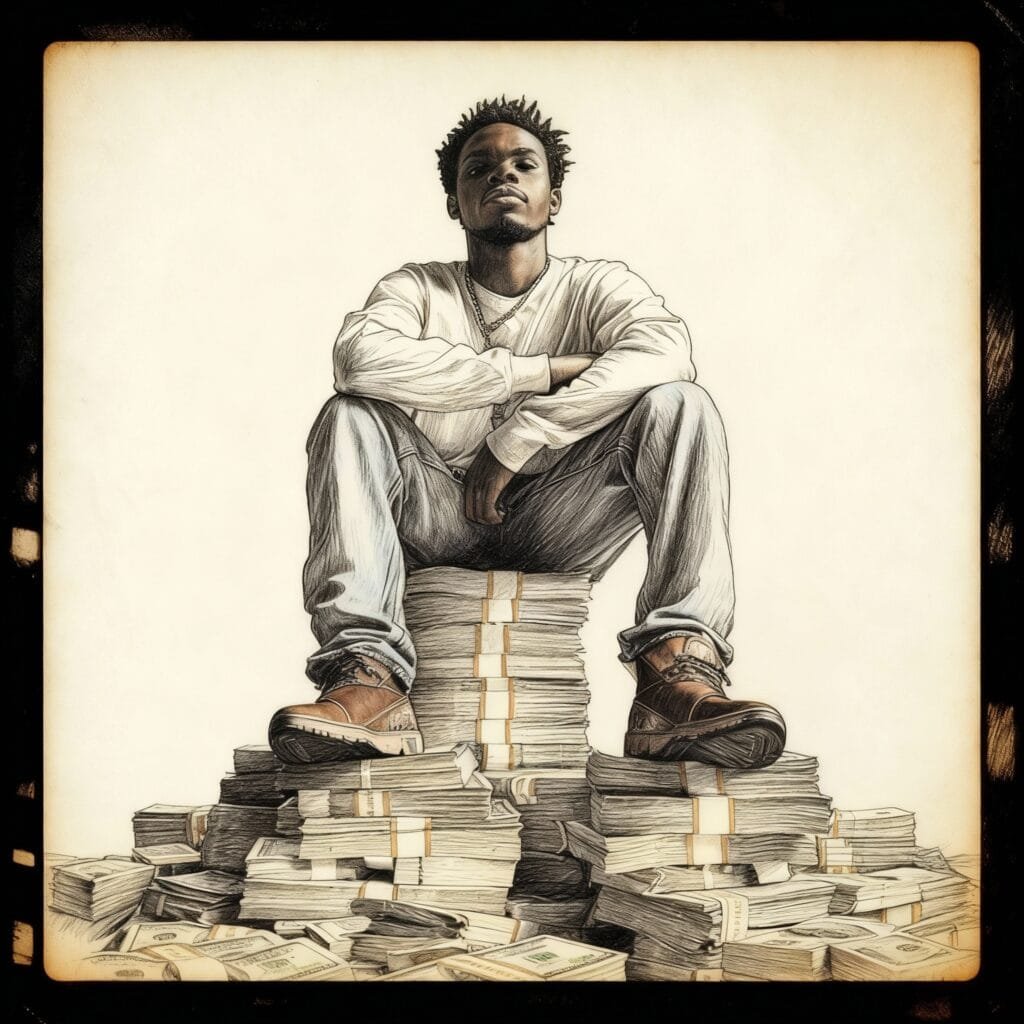

According to Diderot Effect, the most expensive item in your home might not be what you think. It’s not the couch, the television, or even the car in the garage. It’s probably the first genuinely nice thing you bought after getting a substantial raise. Everything that came after was just the universe collecting interest.

This is the strange math of upward mobility. You finally make good money, the kind that once seemed like it would solve everything, and somehow you’re still checking your account balance before dinner. The poverty you escaped has been replaced not with abundance but with a more sophisticated form of constraint. You’ve traded obvious deprivation for invisible obligation.

Welcome to what an 18th century French philosopher accidentally discovered when someone gave him a fancy bathrobe.

When a Gift Becomes a Curse

Denis Diderot was having a perfectly adequate life. He wrote, he thought, he lived in modest Parisian circumstances surrounded by his humble possessions. Then a friend gave him a beautiful scarlet dressing gown, and everything went to hell.

The gown was exquisite. It made everything else in his study look shabby by comparison. His old desk suddenly seemed too plain to sit beside such magnificence. So he replaced it. But then the new desk made his chairs look pathetic. New chairs arrived. Which made his bookshelf an embarrassment. You can see where this is going.

Diderot documented this spiral in an essay called “Regrets on Parting with My Old Dressing Gown.” He had been happy. The gown made him miserable. Not because it was bad, but because it was good. It reset his baseline for acceptable. Everything that was once fine became inadequate the moment something finer entered his life.

This isn’t a story about poor impulse control. This is a story about how a single object can reprogram your entire sense of normal.

The Modern Scarlet Robe

Today, the scarlet robe shows up in different forms. It’s the luxury car lease after the promotion. The apartment in the better neighborhood. The watch that costs more than rent used to. These aren’t purchases. They’re declarations that you’ve arrived somewhere new, somewhere you intend to stay.

The trap springs shut gently. You don’t notice you’re caught because nothing feels wrong. You’re earning more than ever. You can afford these things. The math technically works. But somehow you’re not getting ahead.

What’s actually happening is more subtle than overspending. You’re not buying beyond your means. You’re expanding your means to match your buying. Your lifestyle rises in lockstep with your income, maintaining a perfect equilibrium of almost enough. The finish line keeps receding at exactly the pace you’re running.

High earners often feel more financially stressed than they did making half as much. This seems impossible until you realize that financial stress isn’t about absolute amounts. It’s about the gap between what you have and what your life requires. That gap can grow even as income soars.

The Ecosystem Effect

The real genius of the Diderot Effect isn’t about individual purchases. It’s about how one purchase colonizes everything around it. Buy a nice couch and suddenly you need throw pillows. The pillows demand better lighting. Better lighting reveals that your walls need paint. Your old art looks cheap against fresh paint.

Each item generates a field of inadequacy around itself. The $60,000 car requires the parking spot that costs extra. It needs premium gas, better insurance, regular detailing. It looks wrong parked in front of your old apartment. It practically begs you to move somewhere more appropriate.

The genius of market capitalism is that it understood the Diderot Effect before economists gave it a name. Every product category has tiers. Economy, premium, luxury. Each tier is engineered to make you feel that the tier you’re in is temporary, transitional. Nobody dreams of staying in the middle forever.

This is why furniture stores stage complete rooms. They’re not selling you a chair. They’re selling you a lifestyle that requires that chair plus twelve other things you didn’t know you needed. You came for one item. You leave with a vision of who you could become, if only you bought the right combination of objects.

Identity for Sale

Here’s the uncomfortable part. These purchases aren’t really about the objects. They’re about self perception. You’re not buying a nicer car. You’re buying evidence that you’re the kind of person who drives that car. The purchase is a prop in the story you’re telling about your own life.

We build our identities from what we own because it’s easier than building them from what we do or who we are. Objects are legible. Everyone can see your watch. Nobody can see your character. A nice apartment is proof of success. Inner peace is invisible.

The problem is that identity built from possessions is structurally unstable. It requires constant maintenance and upgrade. Last year’s status symbol is this year’s baseline. The car that announced your arrival becomes just transportation once everyone in your circle drives something similar. You need the next thing to maintain the message.

This creates an exhausting treadmill. You’re not accumulating wealth. You’re renting your own self image from the consumer economy, with monthly payments that never end.

The Peer Group Ratchet

Everything gets worse when you make more money because you start comparing yourself to different people. The cruel joke of financial progress is that it doesn’t buy you contentment. It buys you access to new reference groups who make you feel poor all over again.

At $50,000 a year, you compare yourself to other people making $50,000. Some are struggling, some are fine. You’re probably somewhere in the middle. At $150,000, you suddenly have colleagues making $300,000. You go to parties in homes that cost millions. Your raises, which seemed generous, become barely enough to keep up with the expectations of your new social environment.

This is the hidden cost of upward mobility. You don’t just move up. You move over, into a new comparison set where you’re back at the bottom. Your objective financial position improves while your relative financial position stays roughly the same or gets worse. You have more money and feel poorer. Both things are true simultaneously.

The comparison trap is especially vicious because it’s invisible. Nobody thinks they’re overspending because of peer pressure. They think they’re making reasonable choices appropriate to their station. But reasonable is always relative. Your peers define your sense of normal. Normal defines what you spend.

The Illusion of Arrival

There’s a fantasy that financial life has a finish line. You imagine that once you make enough, the pressure stops. You’ll have enough room to breathe, to save, to relax. This is perhaps the cruelest lie high earners tell themselves.

The pressure never stops. It shape shifts. The person making $60,000 worries about making rent. The person making $200,000 worries about private school tuition and whether they’re saving enough for retirement. Different worries, same anxiety. More money just gives you a more expensive set of problems.

This happens because we treat lifestyle improvements as permanent. Rent a nicer place and you’ll never go back. Upgrade to business class and economy becomes unbearable. Your expectations ratchet upward but never downward. Every gain in comfort becomes a baseline requirement. This is sometimes called the hedonic treadmill, but it’s really the Diderot Effect in motion. Your scarlet robe is now your normal robe. You need something even finer to feel that spark again.

The irony is that people often felt freer when they made less. When your income is modest, your lifestyle is constrained by reality. You can’t afford most things, so you don’t torture yourself considering them. But when you make good money, everything becomes possible in theory, which makes every choice a referendum on your priorities. You can afford a vacation, but should you? What about the home renovation? The retirement account? Every dollar spent is a dollar not spent on something else equally worthy.

Freedom, it turns out, requires constraint. Unlimited options create paralysis. The person with a small apartment doesn’t agonize over which room to redecorate first. The person with a large house is haunted by every unfinished project.

The Irreversibility Problem

The most insidious aspect of lifestyle creep is that it feels impossible to reverse. Try downgrading your life after upgrading it and you’ll discover something unsettling about human psychology. We adapt very quickly to improvements. We adapt very slowly to losses.

Move from a studio to a two bedroom and within weeks you can’t imagine life any other way. Move back to the studio and you’ll feel the loss acutely for months or years. The pleasure from upgrading is brief. The pain from downgrading is extended. This asymmetry makes it functionally impossible to retreat once you’ve advanced.

This is why high earners stay stuck. They’re locked into their lifestyle by their own adaptation. They can’t easily spend less without feeling like they’re suffering, even if that lower spending level once felt abundant. They’re trapped by their own expanded expectations.

The market knows this. It’s why subscription models work so well. Cancel your streaming services and you don’t just lose content. You lose the feeling of having unlimited content available. The loss feels disproportionate to what you’re actually giving up. You’re not losing specific shows. You’re losing the sense of abundance.

The Counterintuitive Escape

Here’s the strange solution. The way out of the Diderot Effect isn’t to buy nothing. It’s to buy the wrong things.

The effect works because each purchase calls for related purchases that fit the same aesthetic, the same tier, the same story about who you are. The expensive couch demands expensive curtains. But what if you pair the expensive couch with the cheap bookshelf you’ve had for ten years? What if you drive the luxury car to the discount grocery store?

This creates what you might call aesthetic dissonance. Your possessions don’t tell a coherent story. There’s no clear tier. And that incoherence breaks the spell. When your home is a mix of nice and cheap, old and new, carefully chosen and randomly accumulated, nothing calls for anything else. There’s no ecosystem to complete because there’s no ecosystem at all.

This sounds like interior design advice, but it’s really psychological defense. You’re protecting yourself from your own tendency to create false coherence. You’re deliberately keeping your lifestyle mismatched so it can’t develop its own logic and momentum.

The truly wealthy understand this instinctively. They pair designer items with drugstore basics. They splurge randomly rather than systematically. They never complete the set. This isn’t because they’re cheap. It’s because they know completion is a trap. Finished is when the spending really begins.

The Question of Enough

The Diderot Effect persists because we never define enough. Without that definition, more income just means more capacity for lifestyle expansion. The empty space fills automatically with new requirements.

Enough isn’t a number. It’s a decision. It’s saying this apartment is sufficient regardless of what you could afford. This car is acceptable regardless of what your colleagues drive. These possessions are adequate regardless of what exists beyond them.

This doesn’t mean artificial deprivation. It means drawing boundaries that aren’t dictated by capacity. You can afford something and still decide not to want it. That’s not the same as not being able to afford it. One is poverty. The other is sufficiency. The difference is enormous.

People fear sufficiency because it sounds like settling. But settling means accepting less than you deserve. Sufficiency means deciding you have what you need. Settling comes from weakness. Sufficiency comes from strength.

The hardest part of making good money is learning that not everything for sale is for you. The market will happily absorb unlimited income. Your job is to disappoint it. To look at what’s available and say no, not because you can’t afford it, but because you don’t need it to be complete.

What Diderot Learned

Diderot eventually looked around at his renovated study and felt something unexpected. Regret. Not because the new things were bad, but because the upgrade came at the cost of something he hadn’t valued until it was gone. Comfort. Unselfconsciousness. The ability to work without worrying about whether his surroundings measured up.

His old study was adequate. It made no demands. His new study was magnificent. It required constant maintenance of its magnificence. He’d traded ease for excellence and discovered the exchange rate was worse than advertised.

The real trap isn’t the spending. It’s the attention. Every upgrade requires monitoring, maintaining, protecting, eventually replacing. Your possessions stop being tools and become obligations. You work to afford the life that the work is supposed to be funding. The means eat the ends.

This is why high earners stay financially stuck. Not because they can’t do math, but because they’re doing math in a game where the goalposts move faster than they can run. They’re playing an unwinnable game and wondering why winning never comes.

The solution isn’t to make more money. The solution is to stop playing. To opt out of the upgrade cycle. To keep the old dressing gown even after you can afford something better.

Not because you’re cheap, but because you’ve learned that better is often just different, and different always comes with a price tag attached to everything it touches.

Pingback: The Ultimate Financial Question: Who Are You Without Your Income? - intellectualfinance.com