Table of Contents

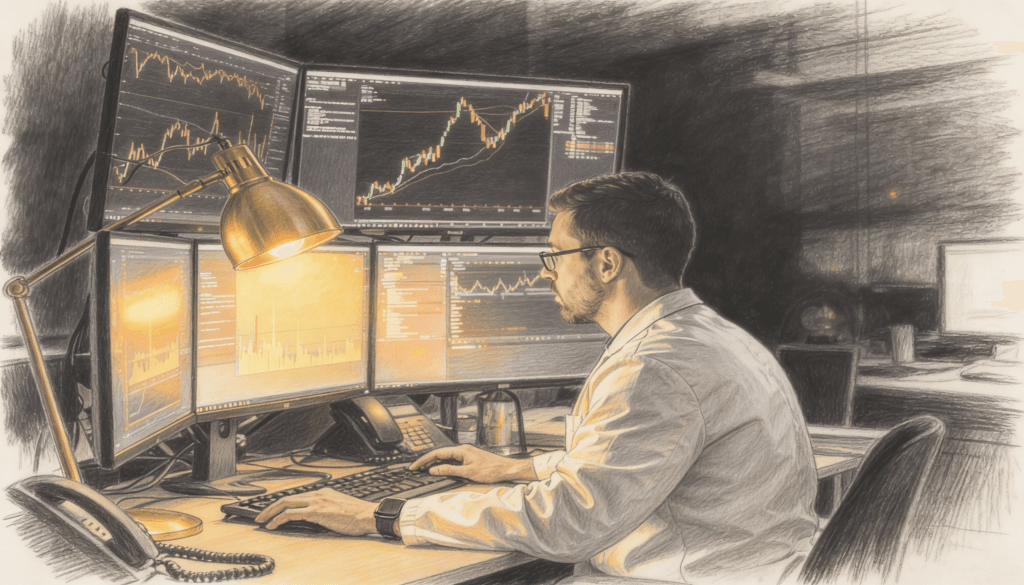

Every quarter, a curious ritual unfolds in the financial markets. Companies report their earnings, and the world watches to see if they “beat,” “meet,” or “miss” analyst expectations. Stock prices surge or plummet based on these outcomes. Fortunes change hands. Headlines blare the results.

But here’s what almost no one stops to consider: the whole thing is theater. The forecasts that drive this drama aren’t designed to be accurate. They’re designed to be wrong in very specific, very profitable ways.

This isn’t a conspiracy. It’s something far more interesting. It’s a game where everyone knows the rules, everyone plays along, and everyone benefits from keeping the illusion alive.

The Fundamental Illusion

We talk about analyst forecasts as if they’re weather predictions. Someone studies the data, applies their expertise, and makes their best guess about what will happen. Some forecasts turn out right, some turn out wrong, and over time we can measure who’s good at this and who isn’t.

This framing is completely backward.

Analyst forecasts aren’t predictions in any meaningful sense. They’re coordinates in a carefully choreographed dance. The companies being analyzed know what the forecasts are. They guide analysts toward certain numbers. They manage expectations like a conductor leading an orchestra. And when earnings day arrives, the “surprise” that moves markets is about as spontaneous as a magic trick you’ve seen a dozen times.

Think about what this means. If you’re trying to predict tomorrow’s weather, the weather doesn’t know what you predicted. It can’t adjust itself to make you look good or bad. But in the earnings game, the company knows exactly what number they need to hit. They can usually control whether they beat it by a penny or miss it by a penny. The forecast isn’t predicting an independent reality. It’s creating a target that the company then aims for.

This is why accuracy, in the traditional sense, is almost beside the point.

The Incentive Map

To understand why forecasts are designed to be wrong, you need to map the incentives of everyone involved. And when you do, a strange picture emerges.

Start with the analysts themselves. Their job, on paper, is to provide accurate information to investors. But their actual success depends on something different: access. An analyst who regularly embarrasses a company by setting expectations too high will find their phone calls going unreturned. Their private meetings will dry up. The flow of information that makes their research valuable will stop.

But an analyst who consistently sets the bar low enough for companies to clear it easily? They become a favorite. Management takes their calls. They get invited to special briefings. They maintain the relationships that make them effective at their job. The irony is thick: being good at the job requires sacrificing the stated goal of the job.

The companies, meanwhile, want to beat expectations without beating them by too much. A small beat looks like well-managed success. A big beat suggests they were sandbagging, or worse, that they don’t have a good handle on their own business. Missing expectations is obviously bad. But exceeding them dramatically raises the bar for next quarter, creating a treadmill that gets harder and harder to stay on.

So companies actively guide analysts toward numbers they’re confident they can exceed by a comfortable but not suspicious margin. This isn’t lying. It’s more like poker players managing their tells. The information is technically true, but it’s selected and emphasized in ways that lead to predictable conclusions.

The Performance Loop

Here’s where it gets truly counterintuitive. This system doesn’t just tolerate inaccuracy. It requires it.

Imagine a world where analyst forecasts were perfectly accurate every quarter. Companies would report exactly what was expected, every single time. What would happen? Markets would barely react. There would be no surprise, no drama, no catalyst for price movement. The entire ecosystem of traders, funds, and media outlets that thrive on quarterly volatility would wither away.

The “wrongness” of forecasts is what creates the game. It’s what generates trading volume, price discovery, and the feeling that information matters. A market that simply confirmed its own expectations quarter after quarter would be boring to the point of uselessness for many participants.

This creates a strange performance loop. Forecasts need to be wrong enough to create movement but not so wrong that they lose credibility.

Companies need to surprise the market but not too much. Analysts need to maintain the appearance of independence while playing along with the dance. Everyone is performing accuracy while actually optimizing for something else.

The Wisdom of Crowds, Inverted

There’s a famous idea that crowds can be remarkably accurate when they aggregate independent judgments. If you ask a hundred people to guess the weight of a cow, their average will often be closer to the truth than any individual guess. This works because the errors cancel out randomly.

But what happens when the guesses aren’t independent? When everyone is watching everyone else, taking cues from the same sources, and optimizing for the same incentives?

You get herding. Analyst forecasts cluster together so tightly that the “consensus estimate” becomes almost meaningless. The range between the highest and lowest forecast is often laughably narrow given the genuine uncertainty about business outcomes. This isn’t because analysts all independently arrived at similar conclusions. It’s because standing out is risky.

An analyst who forecasts high and is wrong looks reckless. An analyst who forecasts low and is wrong looks incompetent. But an analyst who stays near the consensus and is wrong? They were wrong with everyone else.

There’s safety in the herd, even when the herd is heading off a cliff.

This inverts the wisdom of crowds. Instead of independent errors canceling out, you get correlated errors that all point in the same direction. The forecast isn’t the average of diverse perspectives. It’s the endpoint of a social process where conformity trumps conviction.

The Language of Precision

One of the most telling aspects of the analyst game is how precisely wrong everyone is willing to be. Forecasts don’t come in round numbers. They’re reported down to the penny. Analysts will distinguish between an earnings estimate of $1.23 per share and $1.25 per share.

This precision is absurd on its face. The actual earnings of a large corporation depend on thousands of variables, many of them genuinely uncertain. Exchange rates fluctuate. Customers make unpredictable choices. Supply chains encounter random delays. The idea that anyone can forecast quarterly earnings to within a penny is fantasy.

But the precision serves a purpose. It creates the illusion of scientific rigor. It suggests that these are careful calculations rather than educated guesses shaped by social pressures. And crucially, it allows for the possibility of “beating by a penny” or “missing by a penny,” which sounds dramatic but is actually meaningless given the genuine uncertainty involved.

If analysts reported ranges instead of point estimates, the game would fall apart. How do you beat expectations if the expectation is “somewhere between $1.15 and $1.35”? The precision is necessary for the performance, even though it obscures more than it reveals.

The Revision Game

Watch what happens in the weeks leading up to an earnings report. Analysts start revising their estimates. Usually downward. This isn’t because new information suddenly appeared suggesting worse performance. It’s because the game requires a beatable number by the time earnings arrive.

Companies engage in a subtle art during this period. They don’t explicitly tell analysts to lower their numbers. That would be too obvious. Instead, they might emphasize headwinds in the market. They might talk about investments they’re making that will hurt short-term margins. They might simply fail to push back when analysts express caution.

The result is a slow drift downward in expectations, carefully managed to land at exactly the right place. Not so high that the company will miss. Not so low that beating looks too easy. This is expectation management at its finest, and it happens so routinely that it’s barely remarked upon.

By the time earnings day arrives, the “consensus” that the company will beat or miss isn’t really a forecast at all. It’s the outcome of a negotiation that happened in coded language over conference calls and private meetings.

Why the Market Tolerates This

You might wonder why investors put up with this charade. If everyone knows the game is rigged, why does beating or missing estimates still move stock prices?

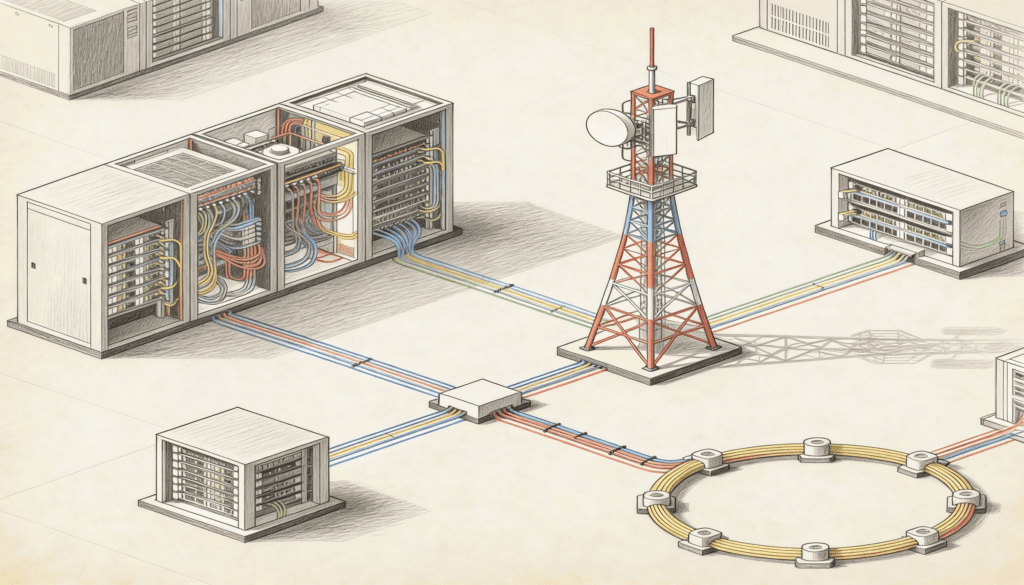

The answer reveals something deep about how markets actually function. Markets aren’t truth-seeking machines, at least not in any simple sense. They’re coordination devices. They help millions of participants converge on shared beliefs that allow trading to happen.

The analyst forecast game provides a focal point. It gives everyone something to react to, a shared reference point that coordinates behavior. Even if everyone knows the forecast is somewhat manufactured, it still serves its purpose as long as everyone agrees to use it as the standard.

It’s like paper money. Everyone knows it’s just paper. Its value is purely conventional, based on shared agreement. But that doesn’t make it useless. The convention is the point.

Analyst forecasts work the same way. Their value isn’t in their accuracy but in their role as a coordination mechanism.

The Winners and Losers

In this game, almost everyone wins something. Analysts maintain their access and relationships. Companies get to manage their narrative and avoid nasty surprises. Traders get the volatility they need to profit. Financial media gets dramatic stories to cover.

But there are losers. Long-term investors who actually care about fundamental value often find themselves whipsawed by quarterly noise that has little to do with the actual long-term prospects of businesses. The focus on beating estimates by pennies can distort management incentives, encouraging short-term thinking over genuine value creation.

And there’s a broader cost to market integrity. When the system runs on managed expectations rather than honest forecasts, it corrodes trust. Sophisticated players learn to see through the game, which gives them an advantage over those who still believe forecasts are genuine predictions. This creates an information asymmetry that benefits insiders at the expense of outsiders.

What This Means for You

If you’re an investor trying to make sense of this, the lesson is clear: don’t take analyst forecasts at face value. They’re not windows into the future. They’re artifacts of a complex social game played by people with very specific incentives.

This doesn’t mean forecasts are useless. But their value lies in what they reveal about the game itself, not in their accuracy as predictions. A pattern of consistently beating estimates might tell you that a company is excellent at managing expectations. A pattern of misses might suggest poor communication with analysts or genuine business struggles that management can’t smooth over.

The earnings surprise that moves the stock isn’t really a surprise at all. It’s the outcome everyone was quietly working toward, a performance where both actors knew their lines.

Understanding this won’t make you a better forecaster. But it might make you a wiser investor. Because in markets, as in life, knowing that you’re watching a performance is the first step to seeing what’s actually happening behind the scenes.

The game continues, quarter after quarter. The forecasts will keep being wrong in their predictable ways. The beats will keep coming. And markets will keep reacting as if any of it were a surprise. Knowing better doesn’t mean you can avoid playing.

But it might mean you play with your eyes open.